Summer in a Unitarian Universalist (U.U.) Church is a fairly quiet but unique time to visit. It’s pretty informal, with services that are low key or have a strong artistic bent. In the summer, it’s customary that U.U. ministers take a sabbatical; they go to the General Assembly, take classes, go on retreats and recharge. We fill our summer months with mostly “Lay Led” services (services led by the congregants). It’s a great time for folks who have wanted to try leading a service, to do it for the first time, or for us to use more experimental styles of delivering our message.

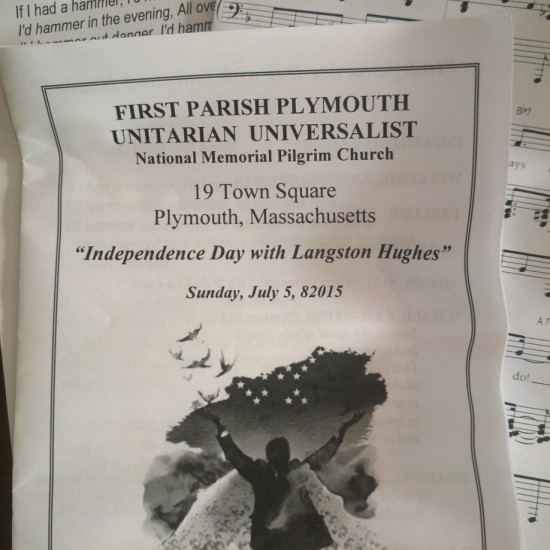

As member of the Worship Committee at First Parish of Plymouth in Massachusetts, I help coordinate, plan and prep for services on Sundays year round and every summer lead a service or two. While I always hope to inspire in my services, the real challenging services are led by our minister; little did I know when I took responsibility for the July 5th service that I would prepare to challenge us all to look at our ‘white’ privilege, and what that charges us to do, through interracial poetry and music.

Having come to be known for a level of theatricality to my services, I was asked months before if I would organize a service whose central message is delivered through a choral reading of something.

“Something” became “Something for Independence Day”, as I took on the July 5 service. It’s been such a tumultuous year for Liberty and Justice; I knew it should laud the ideals of America, (what is a Sunday service without hope?) but it would have to highlight how we are going wrong; the working title became “An Unfinished Democracy”. I found Langston Hughes’ poetry pretty early in the game, but felt, to be honest, intimidated. I wanted to balance the service, feature songs and poetry that represent the struggles of the Black Community, Women and LBGT Folks. I moved away from Hughes, at least for the time being… then, I woke up on June 18 and saw the news.

As the report of the the mass shooting of 9 Black congregants of The Mother Emanuel Church by a 21 year old White Supremacist sunk in, I understood; intersectionality and inclusiveness was put aside, the Ladies could wait, the LGBT folks would have to as well, and as for Mr. Hughes, he got my full attention. I pulled up all his poetry up on the laptop and started reading; any anxiety about Hughes’ very direct, unapologetic anger evaporated, with the news playing and the ping of social media messages in the background.

I still wondered if it was the right thing to do, not because of the tender feelings of ‘white’ people, but because the choral readers would be chosen from my essentially all ‘white’ church. Would it be ludicrous and inappropriate for possibly 4 ‘white’ people to stand up and read the impassioned words of the Black Experience? Would it be considered appropriation and offensive? But a call to arms came via social media, specifically to ‘white’ friends and family. For me, this came from my high school friend, Fanshen. That was all the greenlight I needed….

The Call to Worship was a reminder that Service is a promise we make every Sunday in our covenant that is spelled out in our 7 Principles; it is not just the belief in the inherent worth and dignity of all people, but to affirm and promote the inherent worth and dignity of all people, along with justice, equity and democracy. And that We. Have. Work. To. Do.

After we are called to worship, and light our chalice as we intone our covenant, “Love is the spirit of this church, and service is its law; this is our great covenant: to dwell together in peace, to seek the truth in freedom, to speak the truth in love and to help one another.” We then take the offering and take a moment to share any Joys & Sorrows, and the congregants and guests are invited to come up and either light a candle or, as we did in this service, place a stone in a basin of water. A stone was placed for Mother Emanuel and each of the other churches that were victim to Terror.

We sang hymns, peppered through the service, about building a just and equitable land, the fire of commitment, and that none are free if some are not. We also sang, “If the Spirit Says Do,” an African American Spiritual, and folk activist song “If I Had A Hammer,” which was the last song of the morning. Let me say this about UU and hymns: there a UU joke along the lines of, we can’t sing our hymns loud and proud because we are always too busy reading ahead to see if we agree with the lyrics… but I have to say, these hymns COOKED!

I then shared an excerpt from the A More Perfect Union Speech by then Presidential Hopeful, Barack Obama,

“In the white community, the path to a more perfect union means acknowledging that what ails the African-American community does not just exist in the minds of black people; that the legacy of discrimination — and current incidents of discrimination, while less overt than in the past — are real and must be addressed, not just with words, but with deeds, by investing in our schools and our communities; by enforcing our civil rights laws and ensuring fairness in our criminal justice system; by providing this generation with ladders of opportunity that were unavailable for previous generations. It requires all Americans to realize that your dreams do not have to come at the expense of my dreams…”

The three Langston Hughes poems we recited included, “I Continue to Dream,” “Let America Be America Again” and, my favorite, “Freedom’s Plow” (the one my husband, Chuck, and I cry during our practice readings, one or the others’ voice would break a bit while reading and then would set the other off.) I asked our fantastic musical director, Niles to read with us, as long as he wouldn’t feel like the token POC, and fellow Worship committee and choir member, Linda, to round out our four readers.

At a summer Sunday, services are small, people are on vacations, and what have you. We had 26 congregants and visitors with us on this day, and wonderfully, we had an African American couple just drop in, looking for a progressive church to worship at while visiting the area for the Fourth of July weekend from California (they were a same-sex couple). I didn’t see them right away, being so involved in all the moving parts of the service, but soon I was in the message of the service, in the middle of a reading and I looked up into the congregation and saw them; their eyes were closed, listening deeply, I think I grew three inches taller. When the service ended, we hugged and introduced ourselves; they couldn’t believe that they just happened upon this particular service.

For the benediction the congregation stood and recited in unison from the Declaration,

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Then I closed the service with, “In every community, there is work to be done. In every nation, there are wounds to heal. In every heart, there is the power to do it.” ~Marianne Williamson

I am, perhaps, guilty of some ageism; As it’s an older congregation, I wondered if a generation gap would become apparent for people who were a part of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s. Perhaps I’d be called out as a whipper-snapper telling them to do more; would certain words and phrases bring out defensiveness in these liberal activists or former activists? After all, this is a church that has a reading group who chose The New Jim Crow as one of their books, and led a local Black Lives Matter march… I want to motivate, inspire, move, not discount nor offend but definitely press…

I am proud of my “basically all ‘white’ congregation” for its awareness. Everyone who came up to talk to us after the service told us they were inspired, they cried, they appreciated it’s timeliness, they did not find it hard to speak about White Privilege, or to say the words White Supremacy.

I want this to lead to more, to action; I am joining the Social Action Committee this fall with a couple others, who want to deal with racial issues head on. Our current Social Action committee, do wonderful work, but shy away from controversy. I hope we can shake things up a bit, because we are out of time, people are dying and if what is right is controversial, than that is what we need to be. I think the mindset of our faith community is on track, but we need to create point-by-point actions for those who want to do, but are overwhelmed by the enormity of the problems we are facing. I am at the very beginnings of planning a march from our church (with an invitation out to other places of worship to join us) to the local AME Church, for the fall. Not only to show solidarity but to press our local justice department to address bias. With so much to do, it’s a start.

Poems:

http://allpoetry.com/I-Continue-To-Dream

http://allpoetry.com/Let-America-Be-America-Again

http://allpoetry.com/Freedom’s-Plow

Songs:

If I Had a Hammer www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaWl2lA7968

When The Spirit Says Do https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0OszKIhFRsQ

The Fire of Commitment https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYKPtFPMf7A

Jenn Kanze-Eaton lives by the sea in Plymouth Massachusetts with her husband, incredible teenage daughter’s and three cats, who spent the last 18 years raising her girls, tending her gardens and making old stuff into new stuff. She is an artist, activist,tree hugging dirt worshiper, sci-fi geek and mermaid in disguise.