I grew up in an entirely White neighborhood, in a predominantly White school system, and interacted mostly with my White family members. I watched decidedly Western TV (read: Hannah Montana) and read books with similarly homogenous characters (I still have all 58 of the Hardy Boys books). As I grew older and began my life-long obsession with historical fiction, I identified my history more with the stories of Mary, Queen of Scots and Queen Elizabeth I than I did with those of Princess Chikako of Japan and Princess Jahanara of India. My second grade Ancestor Report described the immigration of my father’s grandmother from Germany to the United States; no mention of my mother’s family was made on that sky-blue poster board.

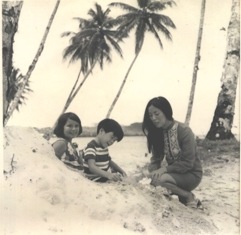

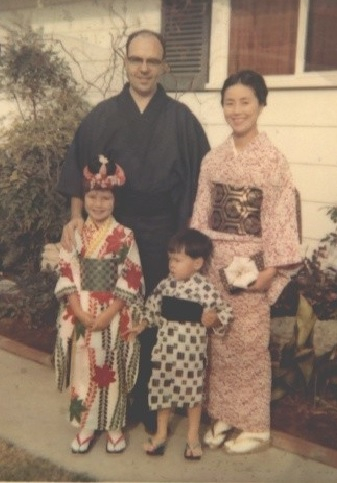

American and European history, however, do not represent the story of all my ancestors. Half of me is graced with my mother’s rich Filipino blood that incorporates heavy Chinese, Japanese, and Spanish influences, a far cry from the Irish and German traditions of my father. Although I was blessed with multiple trips to the Philippines, frequent Tagalog between my mother and aunts, and monthly get-togethers with the local Filipino community, throughout childhood I continued to identify myself as an enthusiastic and whole-hearted Caucasian-American. For a while, I never felt torn between two cultures or thought that others separated me from my neighbors and their blonde hair, freckles, and fair skin. In her essay “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” Audre Lorde introduces the idea of a mythical norm, which in the United States is most often defined as “white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, and financially secure.” She claims that most people acknowledge in some part of themselves that they do not fit that norm – that they are an “other” who identifies differently than that unspoken norm. I did not feel that way. My mother’s heritage simply served more as an interesting accent to spice up my traditional, White, Midwestern upbringing than an inherent part of my own identity.

It was not until the fifth grade when my “otherness” from my own community became a truly salient factor in my own identification. Two young girls about four years my junior, one from Spain and the other from Nigeria, approached me as I waited impatiently in the lunch line for my coveted Thursday ravioli and asked me, with huge smiles on their faces, if I spoke another language. A little taken aback but nevertheless pleased to once again add a little sprinkle of Filipino to my Midwestern community, I replied the negative. Almost as an afterthought, I asked them why they chose to ask me – out of all the other kids in the line –such a question.

“Well – your eyes are a little different,” one replied before scampering off with her friend.

I ran off to my best friend and urgently asked her if she saw something different too. She awkwardly avoided eye contact and told me that “yea – they’re a little smaller than usual.”

And so began my decade-long process of self-definition. Erik Erikson, a psychologist known for his theory on psychosocial development, described this process of identity formation as a “process of simultaneous reflection and observation” in which a person constantly judges herself with reference to how she thinks others judge her in comparison to themselves. That is, I was constantly deciding between which race I “felt on the inside” and how others viewed me. Before that moment, I never thought that I saw something different in my reflection than what my classmates and friends saw. But now I had to choose. Until high school (when “more than one race” finally became an option), I alternated between “Asian” and “White” on standardized tests. It was not an option to embrace both identities simultaneously. When in the United States, I was undoubtedly Asian, as my olive tone and eye structure quickly gave away. When in the Philippines, my towering 5’ 9” frame and fair skin (not to mention that I don’t speak Tagalog) revealed my Whiteness. It was simply a battle I could not win.

As I transitioned out of high school, I intentionally chose the University of Michigan to escape that battle. Beverly Tatum, a prominent psychologist and educator on racial identity, argues that individuals belonging to a “dominant” group do not truly know the experience of “subordinates” due to extensive social segregation in both communities themselves and the wider social sphere (e.g. TV shows, books, movies, etc…). At Michigan, I wouldn’t be in a small, Catholic, White-washed school. I could interact with people from all different heritages and begin to challenge the epistemic dominance prevalent in my own experiences. I immediately enrolled in the class “Growing up Latino/a” because I wanted to engage in a discussion between myself, a self-identified privileged White woman, and those who oftentimes do not benefit from that same privilege. As Audre Lorde argued often occurs with those from dominant communities, I did not want to make it the responsibility of the oppressed to teach me about my mistakes; I wanted to seek out my own role in the cycle of systematic oppression.

The class was a small seminar of about 20 students seated around a round table arranged to facilitate student engagement. Roughly half of the students were Latino or African-American; the other half were Caucasian. As I quickly learned transitioning between Caucasian-American and Filipino-American communities, those who belong to the majority group often do not realize they are the majority until they’re suddenly not. This was certainly evident as I stepped into the classroom for the first time. The unusually high ratio of minority to Caucasian students was immediately salient; the atmosphere was not the same vaguely-interested flavor common to many first days of class. Normal lackadaisical attitude was replaced by an inexplicable edginess. As we each expressed why we wanted to take the class, some students fidgeted uncomfortably. Others did not make eye contact with their peers. Few looked absolutely relaxed. Regardless of their demeanor, the resounding theme was that each one of us wanted to learn about a culture with which half of us had limited to no exposure. It was exciting! I was finally with people who all had different perspectives and were excited and willing to hear about other interpretations of the American experience.

By the next week, every single White student had dropped the class.

Again, I was faced with the dichotomous choice of my racial self-identification. I had identified myself as an “other” in that class, an individual who usually passes with White privilege. I was a White student who enrolled in that class to learn about different minority experiences. But I did not drop the class, as my White peers did. The African-American students did not drop the class, even though they too were delving into a Latino experience different from their own. Did that mean I was actually a minority student, because I did not feel uncomfortable enough to drop the class? Or was I a White student who just happened to be more open to the unusual racial distribution? Or was I actually teetering on the edge of White and non-White, because I was alert enough walking into the room to notice the high proportion of minority students, but not uncomfortable enough to drop the class? I could not go beyond that form of binary thinking. To which group did I belong? Whom did I represent?

As I finished my junior year of college, I finally felt like I had found a rhythm in my college experience. I had found close friends, a welcoming faith community, and a field that I felt passionate about. Never before had I felt so included and welcomed in the university setting. As I sat down with a White Ann Arbor mother in a local psychological clinic, she expressed concern that her young child wasn’t making any friends. That is, he was making friends – just not friends they would usually “find in their neighborhood.” I brushed her oblivious microaggression off, chalking it up to the overprotective tiger-mom persona she clearly conveyed to the psychologist and myself. She was only one mildly racist woman in the otherwise welcoming Ann Arbor. As soon as she left the room, the psychologist turned to me to express her dismay at such a blatantly racist comment. Especially, she said, when someone “not from her neighborhood” was sitting right in the room with her. I looked at her for a moment, confused. Who was she talking about in the room who wasn’t “from her neighborhood?” Only the three of us had been present. Then I realized.

She was talking about me.

I was the person my supervisor (a lovely, kind, intelligent woman) considered “not from her neighborhood.” Never mind that I had grown up in the upper-middle class of Lansing, MI. Or have a two highly educated parents. Or only speak English. Again, my identity formation was challenged as I was forced to confront the difference between how others perceive me and how I perceive myself. To many, I am an “other.” To myself, I was indistinguishable from my Caucasian peers. I believe I have a pretty hefty invisible knapsack that allows me to pass with unearned privileges that many are not privy to. But do I, really? I’ve been pulled over three times and never received a ticket… so yes? I’ve had people tell me to go back to China… so no? I’ve had strangers call me an “exotic flower” … so maybe?

Perhaps the answer, though, isn’t so easy. I am Filipina. It would be an insult to my mother and our family to deny the history that has been such a formative part of my mother’s life, and consequently, my upbringing. Yet I know without a doubt that I do live a privileged life. I’ve always assumed that neighbors will be pleasant to me. I feel comfortable wearing used clothing without people attributing that choice to my race. I’ve never had trouble finding makeup that fits my skin tone. So, perhaps, this dichotomous approach between White and non-White does not fully account for the identities that shape who I am. Maybe, after all, I am not either White or non-White. Maybe I can be an “other” in the communities in which I live, yet still experience White privilege because I am not only an “other.” And I am not only White. I am an entire being made of the intersection of experiences that have formed my world perspective, including experiences of privilege, marginalization, and some hazy in-betweens. These experiences cannot be so easily binned into two categories. Perhaps then, social expectations that so definitively categorize entire identities, including entire social movements, do not give justice to the depth of the populations they serve and their intersectionality. Maybe social justice itself, at least in part, is the process in which individuals acknowledge and engage in their intersecting identities, combine them with those of others, and use that more comprehensive viewpoint to instigate change and awareness in their communities.

Everyone has a variety of intersecting identities that shape the way he or she views the world and interacts with others. Gender, sexuality, race, and able-ness are only a few of the identities that people can claim to be their own and that can affect the way individuals interpret their world. Many people grow into adulthood fully aware of their many overlapping identities. I did not. I am continually adjusting my interpretation of myself in terms of both race, womanhood, social class, and education and reflecting on the ways different interpretations of these identities affect how I present myself to society and how society views me. And this, in a narrow lens, is the foundation of social justice. Social justice relies on both the process through which individuals and communities can reflect on and acknowledge themselves as a coalescence of many identities as well as the progress we’ve made to empower that coalescence. I have realized that I don’t need to neatly bin myself into White or non-White. That simply doesn’t do my person justice. I am a White, Filipina, educated young woman…and so much more.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Andrea Maxwell was born in raised in the Lansing, MI area. Her mother grew up in Cagayan de Oro in the Philippines, and her father is originally from Indiana and is of Irish and German descent. Andrea is currently a senior at the University of Michigan studying Neuroscience and Psychology and is interested in the intersection of biology, psychology, and social justice. She hopes to serve as an advocate for human rights through both clinical and research involvement in the mental health field.

Megan Rudnik received her B.S. in International Business with a minor in Spanish and her MBA from Winthrop University. Since graduating, Megan spent 2 years in the eace Corp, serving in Panama. She also recently completed 4 months in China teaching English.

Megan Rudnik received her B.S. in International Business with a minor in Spanish and her MBA from Winthrop University. Since graduating, Megan spent 2 years in the eace Corp, serving in Panama. She also recently completed 4 months in China teaching English.