Despite feeling comfortable verbally sharing my story with friends and students it has taken me 15+ years to publically write about it despite numerous kind nudges from others. Somehow “putting it out there” in written form has always been somewhat of a foreboding experience that has kept me paralyzed in fear—that others may respond critically and perhaps like so many times before that those I identify with will reject me. So it is my hope that these words will encourage others to share their own truths, shake off fear and move forward embracing the freedom that comes from breaking free of silence…

Part II.

“From Turkish to Mixed”

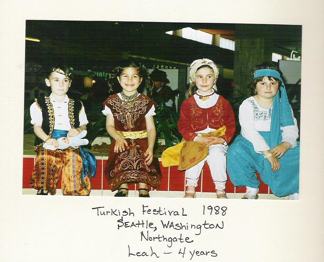

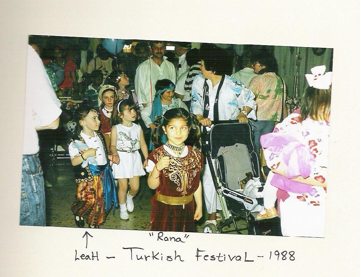

As a child, I knew that my dad was from Turkiye and that this meant I was “Turkish.” At such a young age all I could equate “being Turkish” with was being forced to wear “weird” clothes in cultural festivals once a year, receiving gifts and letters from my babaanne (father’s mother) that went unread until they could be translated and playing with my one Turkish friend (whose mother my mom became close with while taking language lessons from her).

I carried around this identity without much thought for most of my childhood. Once my mother married my stepfather and had my brother, we interacted less and less with the Turkish community. With my mother working full-time and commuting 3-4 hours a day my Turkish identity only surfaced occasionally- most frequently at cultural events for school or when I brought store-bought baklava to potlucks.

Around middle school, this identity started to take on more meaning for me. Having been raised in predominately white, middle class, heterosexual, Christian spaces where most knew little or nothing about my father’s background no one ever queried much into the racial/ethnic identity I carried due to my fair complexion. There was often confusion around my last name differing from the rest of my family and my relationship to my younger brother whose blond hair and blue eyes stood in stark contrast to my own, but not to the extent of questioning my “whiteness.”

While I knew my mom, brother and stepdad were white, I personally had never given much thought to my own identity nor identified as “white.” I began to get frustrated that I did not know an entire half of my family—that I could not communicate with them without assistance, that I knew nothing of their culture, religion or location and I began to reject my “whiteness” and to solely identify as Turkish. As I entered high school I became increasingly angry at the lack of understanding I had of my family and self. In an effort to help, my mother contacted the family of my childhood Turkish friend and informed them that I wanted to learn more about my dad’s culture. They immediately invited me to participate in a Turkish fashion show. Excited I went to their home only to come back in tears as her mother had spent half of the rehearsal telling others to speak in English for me. Rather than feeling a sense of belonging and solidarity, the experience only further solidified that I truly was an outsider in both worlds.

When I returned to school after the weekend, the assistant principle, who happened to be at the fashion show, decided to pull me into his office to question my racial/ethnic identity and tell me about his Turkish immigrant wife before asking me to be a buddy to an incoming Turkish international student. Surprised and agitated I tried to explain that I was American and had little connection to my Turkish heritage and that any student on campus would be about as much help to the new student as I would be. The student either never came or something I said convinced him that it was not something he should further press me about, as I never did meet the student.

While I’m sure he had the best of intentions and likely thought he was being “progressive” by learning about his wife’s culture and trying to connect people from the same racial/ethnic background this interaction simply illustrated to me that he considered all of “us” to be the same and was yet another situation in which my lack of connection to my heritage was exposed.

Throughout high school, I continued to wrestle with my identity. The first two years I began to make new friends, most of whom identified as Mexican, Black or biracial. Within this group, I felt more comfortable exploring and expressing my emerging racial/ethnic identity. However, this was not without it’s own bumps in the road such as when discussions about “white people” arose. I sometimes shared certain sentiments, but felt conflicted. I would remind my friends that my mom and stepdad and brother were white and I was half white as well. This was usually met with a comment such as, “Well you’re different because you’re mixed.” I’d sit there thinking, “You’re still talking about my family…” Eventually I started to realize that my stance of rejecting whiteness via distancing myself from white people was incompatible with loving my family and myself.

My junior year of high school I began an early college program and started attending community

college full time. I remember one of my first courses was post civil rights history. The professor had us do an assignment that required us to interview family members about our cultures and history. Unfortunately, I was only able to complete half of the assignment. Once he found out that I knew little of my dad’s heritage and my own culture he went on a mission to “help me find it” and avoid assimilation! That day, we went around the entire campus until he found another Turkish student and left me with her. We had a polite but awkward conversation, which did little in helping me “find my culture,” but did serve to further highlight my status as an outsider.

After the awkward encounter I quickly found my way to the multicultural center, which soon became my home away from home (I literally slept there in the morning before classes to avoid traffic). I began to gain an eclectic group of mostly African and Middle Eastern international friends, two of whom were other bi/multi racial women. One was of a Turkish Pakistani background, but was raised in America and another, Amnah, shared almost the exact same story as myself except her father was from Dubai and she phenotypically did not pass for white. I was elated to finally have a friend who understood what it was like to be raised in a white American household, while wondering about the other half of your family and identity. Amnah and I quickly became close friends and sought out a cultural organization to join.

At the time, there were few cultural student organizations on our campus. The closest one to being multiracial was the Muslim student union, which was comprised mainly of international students from numerous countries. However, being raised in Christian households, Amnah and I didn’t see this as a group in which we would fit in. Despite neither of us identifying as black, many of our friends were in the Black Student Union, so we decided to ask if we could join. While we may not have identified the same racially we connected with many of our friends in the BSU as most of our parents/families were recent U.S. immigrants.

Once a year the multicultural center nominated a set number of students to attend the annual community college students of color conference. It was through these conferences that I found my way to the multiracial community. The MAVIN Foundation was just taking off in Seattle and they held a session at the conference. It was the first time I had seen a session description that I could really relate to and was elated. However, the students of color conferences were not all filled with fun, camaraderie, understanding and laughter. They were also places that brought out pain, frustration and reaffirmed boundaries.

I can still recall one particular incident in which I was reading a book in the hallway when another attendee approached me and began to engage in conversation. Unbeknownst to me he was conducting an authenticity test under the assumption that I was a white girl wearing a “black” hairstyle. Once he found out my racial/ethnic identities he began to go on and on about how he was wrong and how “my people” were actually one of the most targeted and oppressed groups due to the anti-Middle Eastern sentiments shared by many Americans post September 11th. That evening he expressed his interest in dating me. I found it interesting and perplexing that despite being the same exact person, within a matter of minutes, in his eyes I suddenly went from being a white girl engaging in cultural appropriation to a mixed girl who was beautiful and acceptable for a man who believed in Pan-Africanism to date. Reminded of the old familiarity of high school lunch conversations, this was not the first or last time I’d be told that one part of me redeemed the other. Those giving the “compliment” never seemed to understand how it could be interpreted otherwise and I could not understand why it still sometimes felt affirming.

When reflecting on these experiences I often recall a conversation I had with a friend during which she said, “Your race is part of who you are, but it is not all of who you are.” I think that was the beginning of my realization that being a fringer was okay. Not fully understanding my culture was okay. Letting go of societal labels and expectations of who I was and should be was okay. There would be many more uncomfortable and life changing experiences to come, but I was the only one who could define myself and regardless of who or what others perceived me to be, all that mattered was that I knew who I was—a mixed, frequently white passing, second generation American sociologist, who knows more Spanish than Turkish, loves spoken word poetry, 90s R&B and Rap, boxing, is still a fan of The Seattle Super Sonics and Allen Iverson, watches obscure documentaries, wears giant earrings and is obsessed with dog advocacy. I am a kaleidoscope of the sum of my social identities, experiences, interests, and talents, yet none of them alone adequately define me. I am happily indefinable.

Naliyah Kaya is the Coordinator for Multiracial & Multicultural Student Involvement & Community Advocacy at the University of Maryland College Park where she works closely with Multiracial/Multiethnic and Native American Indian/Indigenous student groups, serving as an advocate for the needs of these communities. She currently teaches TOTUS Spoken Word Experience and Leadership & Intersecting Identities: Stories of the MULTI racial/ethnic/cultural Experience.

Naliyah Kaya is the Coordinator for Multiracial & Multicultural Student Involvement & Community Advocacy at the University of Maryland College Park where she works closely with Multiracial/Multiethnic and Native American Indian/Indigenous student groups, serving as an advocate for the needs of these communities. She currently teaches TOTUS Spoken Word Experience and Leadership & Intersecting Identities: Stories of the MULTI racial/ethnic/cultural Experience.

As a poetic public sociologist, Naliyah utilizes poetry as a medium for teaching and social change. She encourages students to engage in artistic expression as they examine their own identities, beliefs and values and as a form of activism in promoting social justice. It is her hope that through this process of self-exploration students will embrace cultural pluralism, find commonalities across differences and engage in research and dialogues that seek to benefit the greater good of society through positive social action.

A native of Washington State, Naliyah grew up just outside of Seattle. She earned an A.A.S. from Shoreline Community College, a B.A. in Sociology from Hampton University, and received her M.A. & Ph.D. in Sociology at George Mason University. Her poetry has been published in Hampton University’s literary magazine The Saracen, George Mason University’s Volition, Voices of the Future Presented by Etan Thomas and Spindrift Art & Literary Journal.

Learn more about Naliyah and her work on her website.