Being brown and having a white dad means something, whether people want to acknowledge it or not. Right now, I’m working on an anthology project—“WHITE DADS: Stories and experiences told by people of color, fathered by white men.” I’ve been loving the ways people are taking this idea, supporting it, and helping it grow. Thing is, though, absolutely none of us have the same story to tell about what it’s like being brown, raised by a white guy in a society that ranks validity based on melanin and race. This is a part of my story and the story behind WHITE DADS.

Answers are never just black and white–but in the case of biracial identity, sometimes, that’s exactly what they are.

When I was about five years old, I learned the phrase, “Pedestrians have the right of way.” To me, this translated to, “I am going to walk into the road, and you have to stop.” So with all the wonder and arrogance of a new kindergartener, I unfortunately made habit of walking out into traffic with the confidence of a queen. My mother calls this my “Bad Seed” phase. My older sister had to literally grab me by the shirt and yank me from harm’s way as cars backed out of the driveways I didn’t care to notice.

One evening in 1996, I was on out on a stroll with my dad downtown. While I don’t recall it being a particularly bustling evening, I know there must have been enough cars buzzing by to practice caution when near the road. What I do recall, though, is that I was being a brat, most likely because I didn’t want to hold my dad’s hand. I was probably insulted by the sheer fact that he thought I needed help crossing the street at all. Didn’t he know I had the right of way?

I broke away from his grasp and took off tearing down the darkening street. My dad, 6 foot tall, took off running right behind me, no doubt yelling for me to “get back here!” You’ll have to catch me first.

And then, right as the chase was getting underway, I almost ran right smack into a young couple out on a date. The woman was almost frantic.

My dad has told me about the brief interaction he had with that man and woman, all those years ago. Now, he laughs at this story.

“Those people thought I was trying to kidnap you!” he bellows.

It’s funny, you see, because I was little brown girl, being chased by a big white man on a darkish, half deserted downtown street.

I laugh at this story, too. My dad may be a lot of things—someone who, for example, doesn’t fully understand racial fetishization or the panicked terror of police brutality against people who share my skintone—but a stranger or my kidnapper is not one of them. How could those people not see that?

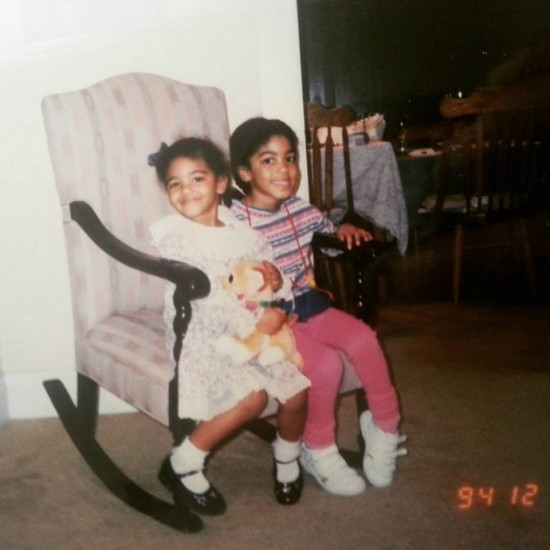

I’m African American on my mother’s side, and I’m a Russian, Polish Jew from my father. In a world where we’re so often told black and white issues don’t exist, I have been coerced into telling the world that’s exactly what I am: A black and white issue.

I don’t have my father’s hazel eyes or his ruddy, pink cheeks. I’m a brown girl, not as nearly as light as my father or quite as dark as my mother. I’ve got my mother’s melanin and big, brown eyes. My sister has the high forehead of the Native Americans we’re mixed with from our mom’s side of the family, and I’ve got the babushka face from my ancestors in Eastern Europe from our dad’s. You probably wouldn’t guess that’s why my cheeks are so round, though. And why would you? I’ve got my mother’s melanin and big, brown eyes, and that’s what people see. When I’m asked that degrading, yet common and impolite question, “What are you?” I know what they’re really asking is not “Who are you?” but, “What made you that color?”

The idea of having my father mistaken for a stranger wasn’t something that really registered with me until I was older. My mom and I were both brown, but my dad and I were both Jewish. Two of a kind on either side. It wasn’t until I was older that the fact that I didn’t get to be in control of how other people saw me, and by extension what they saw when they looked at my dad and I, honestly came as a shock of hurt. Because we didn’t immediately register as looking like the family unit norm, society told me that he and I weren’t two of a kind after all; not really.

I came to realize that rather than being seen as unique individuals, people of color are seen as a blur of the narratives and stereotypes centered around our ethnicities. This is the kind of faulty thought process that has led so many people to ask me, “How can you be Jewish if you’re black?” Or worse, the definitive, “Black people aren’t Jewish.” There’s always this opposition of my identity. I’m either too black to be Jewish, or too Jewish to be black.

In our society, black people don’t get to be dynamic. Black people don’t get to be seen as diverse within the general population. We’re seen as one big lump mass of the same experience, “The Black Experience,” it’s often called. And if you don’t fit neatly into that preconceived fold, the immediate conclusion is that there’s something wrong with you, not something wrong with the narratives that have been concocted around race identity. There’s this false idea that we all have the same, one story to tell from start to finish. We don’t even get to claim an ancestral nation most of the time. People simply say, “Africa,” like it’s all the same. And because we’ve been stripped of the privilege of knowing those nations, that’s almost just what it’s become. We don’t get very many opportunities to be seen in the mainstream as individuals. We’re used as diversity, but not seen as diverse.

In parallel strides to the systematic and institutionalized racism that’s rampant in our country, this is a colorist society. “White” is typically and continually seen as the default race—even down to little things, like the color “nude” being a light skin tone—and it’s seen as the opposite of brown. Again and again in our male-run world, white men are the gatekeepers who make the decisions for us all. It’s obvious and undeniable that they’re the demographic with the most privilege in our country, and more often than not, the antagonists in stories about seeking social and racial justice.

These are things I know to be true about the climate of our world. My dad and I both know that they’re true. But what it also means, on a personal, individual level, is that I, a young, black woman, am seen as the the opposite of the older white man who is my father.

Enter WHITE DADS. This is the push back, the retort, the response, the healing process. This is a chance to share, laugh, process, and expose the immense diversity that exists in our communities, even within this one sliver of racial identity. This is a chance to tell our stories and say that we, the people of color with white dads, are valid, strong, and that we are not fractions of mismatched cultures inside a single being. We are whole, and who we are is enough.

Don’t let the specificity of the title fool you. In fact, it’s meant to be provocative. In some ways, it’s at odds with itself. Having to preface “dad” with a label, an explanation, can be an othering experience all it’s own. The theme may be specific, but it is by no means narrow.

On top of that, these days, so many brown folks are united under the “people of color” umbrella. This kind of budding unification is an astounding display of support. By choosing an often overlooked focus, potential is created to expand that unification in new ways and to publish those who are bursting at the seams with untold stories.

WHITE DADS is accepting all forms of creative expression from black, brown, mixed race, adopted and/or POC who have the unique experience of having a white father. This is meant to be an intentional, creative opportunity to speak on truths, tell stories and share art that fall within the thematic focus.

I’m tired of defending who I am. Fighting white supremacy and patriarchy, two things I care greatly about, are political issues I invest a lot of myself into. At the end of the day, though, theory, “-isms,” and social constructs are not going to make my dad less of the father who raised and loves me. These are political issues. My relationships with my family are not.

It’s isolating be unsure of where your identity lies.There is not a universal truth or a simple answer. This project, like identity itself, is far too nuanced and complicated to ever be restricted to binary modes of thought; to ever be about just one thing or another.

These are matters I recognize to be authentic about my own story and experience, but there’s so much more to say. WHITE DADS can be a place for those stories to be told. It’s a space to explore the crossroads of where social and political constructs intersect with personal experiences and family, loving or otherwise; an opportunity to look into the nature of identity and family ties that are anything but black and white.

Submissions are open from Dec 1st, 2015 – Jan 15, 2016. Check out the WDZ Tumblr page for more information. Email whitedadszine@gmail.com with questions. Find more writing from Sarah here.

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.

Visit white-dads-zine.tumblr.com for more information on Sarah’s latest project, or email whitedadszine@gmail.com

Ravishly

Huff Post Blog

Racialicious

Twitter: @happyrocktalk

Robert Farid Karimi

Robert Farid Karimi Crystal Shaniece Roman

Crystal Shaniece Roman Carly Bates

Carly Bates Zavé Gayatri Martohardjono

Zavé Gayatri Martohardjono Lisa Marie Rollins

Lisa Marie Rollins Fred Sasaki EAT TO JAPANESE: Achieving ethnic authenticity by eating, shopping, emojis

Fred Sasaki EAT TO JAPANESE: Achieving ethnic authenticity by eating, shopping, emojis

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.