Some things are forever intertwined.

It was February, early spring in Tucson – cool, dry and pleasant. A slight breeze whistled through Palo Verde and Cottonwood trees. Barbecue grills were fired up – kids were playing in the streets.

Our neighborhood was bursting with unbridled anticipation, murmurs gaining resonance with the news that the Fiesta de Los Vaqueros Rodeo was in town. Soon, there would be a parade, marching bands, majestic horses, and a celebration of Mexican and American cowboys. For a desert kid, this was a very big thing. Cowboys were bigger than life. But this year, I would not attend. I was at another event, not far from the planned festivities.

I was five years old and too young to be allowed into the ground- floor hospital room where Francisco, my Abuelo, an authentic cowboy – lay dying. He was old now, sick and frail; and his passing not totally unexpected.

Relatives arrived, throughout the day to pay their last respects. They would pass by my twin sister Linda and me in the hallway, compelled by relation, to cup our faces, or pat us on the head as they came and went. All preoccupied with private thoughts, a lapse that left us momentarily unattended.

Given the oversight and driven by a heartfelt desire to see our grandfather, Linda and I didn’t dawdle. We bolted out the building – me in my little-boy cowboy boots and chaps, Linda in her tasseled vest and matching skirt, and into the pomegranate tree-lined courtyards that dotted the hospital grounds.

Too short to peer into the rooms directly, we jumped, hopped and crawled up brick ledges, peering into windows, startling patients and visitors alike. A menacing looking nurse in a stiff, starched, white linen uniform caught us peeking, stuck her arms out the window and attempted to grab us.

Scolding us, she waved her finger and shouted, “¿Qué estás haciendo niños, ¿dónde están sus padres?” (“What are you doing, children? Where are your parents?”).

She was a big woman, with a prominent mustache and crooked yellow teeth, and she scared the bejeezus out of us – but it only served to hasten our search for our grandfather.

We knew our parents would certainly be looking for us by now. One last courtyard, one last hospital wing to check; not this one, not that one. Wait… “I found him,” I shouted. Linda was across the courtyard, tired and walking slowly now.

I crawled up to the window ledge, and there was Francisco propped up in his bed, alone and abandoned, everyone else no doubt frantically searching for us.

I tapped on the window, and he slowly turned my way. At first he didn’t see me, the top of my head barely visible over the window ledge. But I climbed higher; my chin pressed against the glass. And then with a raised eyebrow, he saw me, and his eyes locked onto mine.

The old man still had some magic in him. He sat up erect, smiled, winked, picked up his sweat-stained cowboy hat that lay on the nightstand and waved it high above his head.

From one cowboy to another, “I see you, little man,” he seemed to say. Tears rolled down his weather-wrinkled face. I thought, “Is he happy, or sad?” But he smiled again, as did I. A moment forever shared, frozen in time.

By now my Aunt had entered the room, and my Mom and Dad in hot pursuit were in the courtyard with Linda in tow. They walked up to the window I was clinging to, and as parents are wont to do with disobedient children, swatted my behind. Small price to pay for finding Francisco. I climbed my Father’s arm until he and Mother relented, and lifted us up so we could wave and say goodbye to our Abuelo. Sadly, he died later that day – peacefully – with family surrounding him.

I’ve thought of him often over time, heartened in no small part by my resemblance to the old man. I always wondered how he ended up in the southwest. I discovered Francisco Wilson’s clan had its origins in the Celtic Euro-Iberian Peninsula (northern Portugal & Spain); his ancestors eventually voyaging up the Atlantic coastline to southern England.

Francisco’s father, Baldomero, was the son of a Cornish miner who immigrated to Mexico from the Southwestern Brythonic region of Great Britain in the early 19th century. The Cornish miners were the best hard-rock miners in the world, but depressed economic and metal markets in Europe forced many to emigrate to mining regions throughout the world. Specifically, to Latin American silver mining locations, of which Alamos, Mexico, was one, and where Baldomero lived and worked and where Francisco was born.

Our Celt ancestors were from an ancient civilization, and according to chroniclers, emerged from the lower Danube region. They can be traced back to what are now Germany, Italy, Greece, and the Iberian Peninsula. They sacked Rome in 387-386 B.C. and the following century destroyed the armies of Macedonia in Greece.

Proponents of the Druid religion they believed in the immortality of man. The Celtic Clan, specifically the Cornwall and Cornish peoples, were documented to have lived from circa A.D. 400, half a Millennium prior to the origin of England, until around A.D. 890. They are a distinct ethnicity separate from most of England’s Anglo-Saxons. The Cornish part of our family emerged from this civilization.

The fact that Francisco was Celtic Cornish, a Mexican native and didn’t speak a word of English when he arrived in the United States, was equally surprising and enlightening. (The irony, of course, is that the Cornish people also had their language before their assimilation into the dominant English-speaking culture.)

He eventually emigrated from Mexico to Arizona, a U.S. territory, in 1909 to escape the Mexican Revolution that pitted the repressive dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz against a populist uprising led by Pancho Villa and Emilio Zapata. Francisco enlisted in the U.S. Army during WWI and eventually settled to a life of farming and ranching in southern Arizona.

Having discovered all of this gave new meaning to me about Francisco’s life. I’ve come to believe his waving his hat farewell was a final attempt to bond with his niños pequeños. He wanted to make certain he had linked the past with the future before he left. He was his father’s courier, with a history to pass on, and I’ve accepted as true, a belief that I was his chosen if at the time, unknowing recipient.

Over the years, I’ve sheltered and safeguarded the significance of Francisco’s mortality and transience – it has kept me grounded and provided me with purpose and perspective.

I revisit my Abuelo when in need of counsel and when my relationship with my son needs affirmation. My eyes, or are they Francisco’s? – Lock onto his. There’s no escaping legacy – prescient in knowledge and history.

My son, you will listen to and remember what I say. Many people have come before you. A host of fathers with different names from different lands foretold your life. They crossed continents and braved perilous sea voyages across the world. They trekked on foot through mosquito-infested Yucatan jungles and swamps, survived tropical diseases, climbed over the Sierra Madre Mountains and across the Sonora desert to give breath to your life.

You are their legacy. Don’t run away from it. Embrace it. It’s your inheritance. Pass it on.

My childhood memory of Francisco helped put my family tree into focus, connecting the links between mixed-race and multicultural people proud of their origins and working class, embodied by miners’ hard hats and ranchers’ Stetson hats. Kindred spirits, a cowboy thing.

I’ve long since traded horses for Subarus and Jeeps. But the memory of Francisco remains forever sheltered in this little boy’s heart.

It’s been many years since I last attended Tucson’s Fiesta de Los Vaqueros Rodeo. But I will, if only to pay homage to Francisco’s (and my) heritage and the lifeline he bequeathed to yet another Wilson generación.

Frederico Wilson is currently the owner and President of an International Fluid Power Procurement and Sourcing Company; founder of a non-profit organization (under development); blogger at mestizoblog.com, focusing on multicultural perspectives and issues. He is a USAF veteran (environmental/missile inspection specialist); and former domestic and international professional in the Airline, Telecommunications, Sales, and Financial Securities industries. Originally from Arizona, he is a lifetime student of cultural anthropology and applied behavioral science. He attended Arizona Western and the University of Arizona and holds numerous military technical, and corporate management certifications and licenses.

He is of mixed Mexican, Indian (Yaqui Tribe), Euro-Iberian, and Cornish Celtic ancestry. He lives, works, and writes in metropolitan Seattle, Washington.

He is best described by a quote attributed to Anthony Bourdain when recounting the preparation of a Burgundy wine-base rooster entrée.

“So, they take this big, tough, nasty-ass rooster, too old to grill, too tough to roast. Marinate and simmer the shit out of it, before it’s tasty.”

Frederico is the author of a new book, Escaping Culture: Finding your place in the world. Find out more on his website: mestizoblog.com

Robert Farid Karimi

Robert Farid Karimi Crystal Shaniece Roman

Crystal Shaniece Roman Carly Bates

Carly Bates Zavé Gayatri Martohardjono

Zavé Gayatri Martohardjono Lisa Marie Rollins

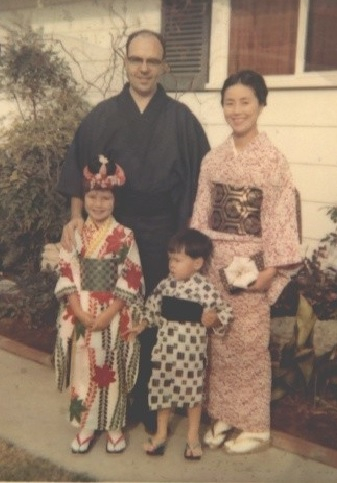

Lisa Marie Rollins Fred Sasaki EAT TO JAPANESE: Achieving ethnic authenticity by eating, shopping, emojis

Fred Sasaki EAT TO JAPANESE: Achieving ethnic authenticity by eating, shopping, emojis