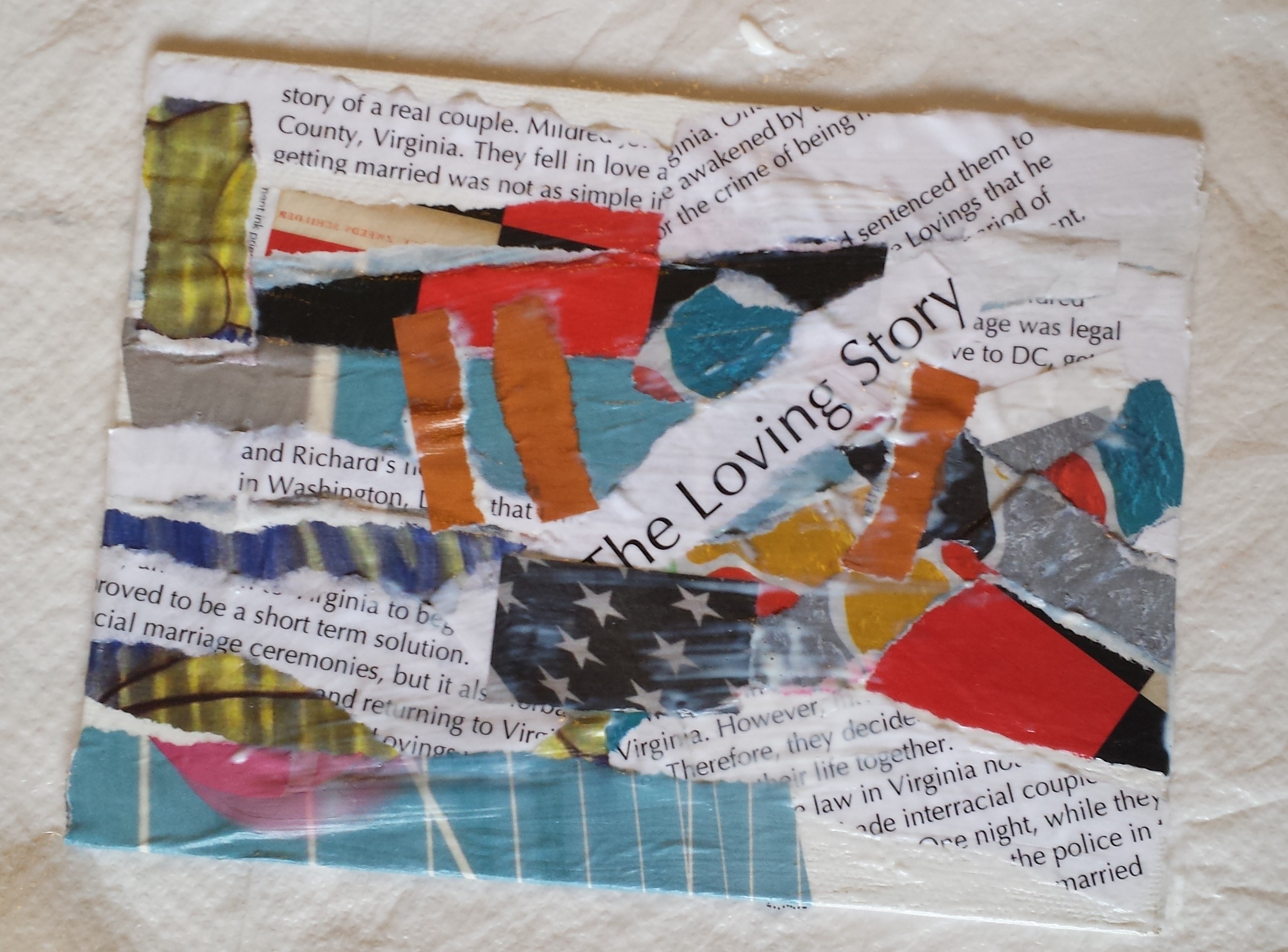

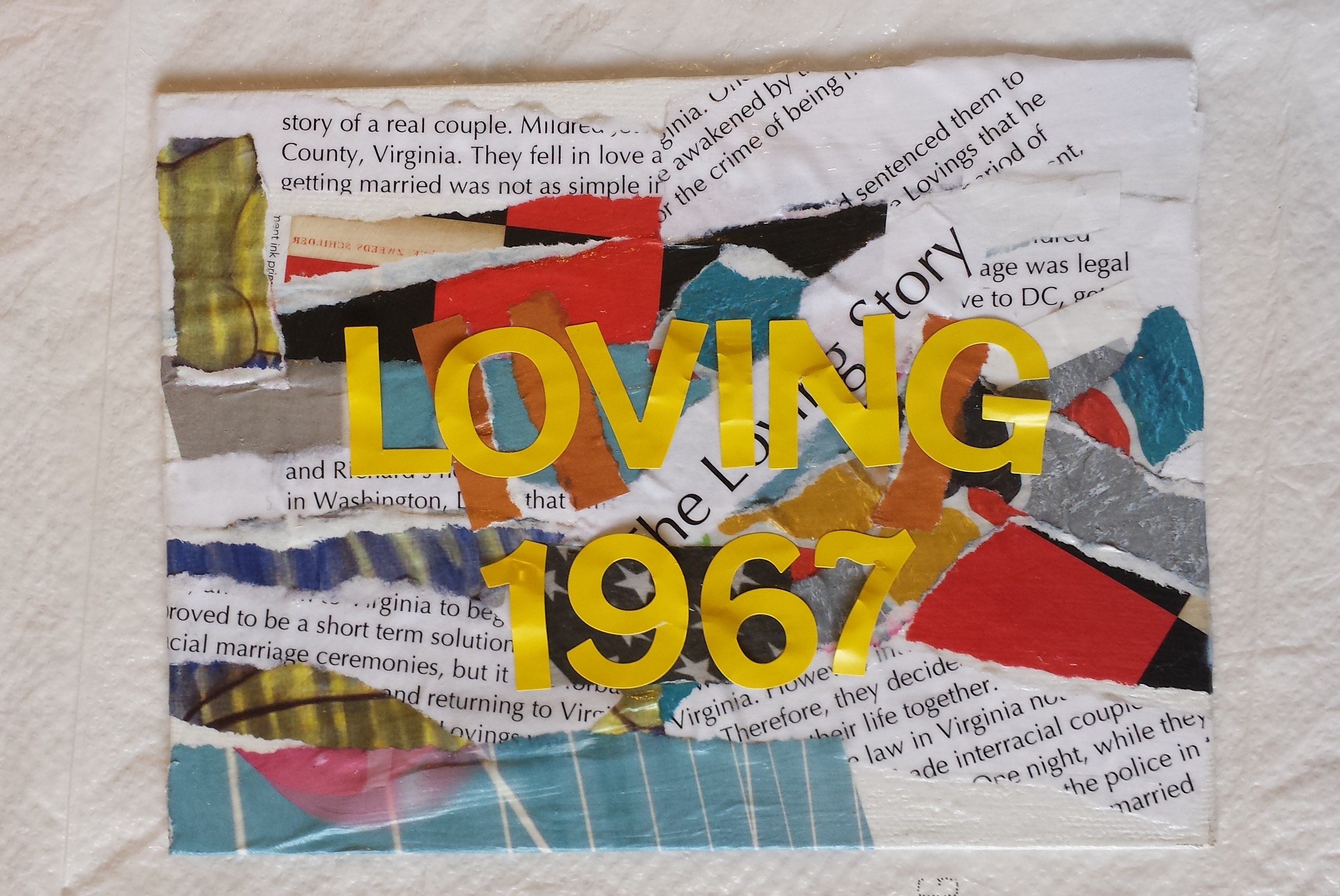

What does it mean to call a family blended? The term still refers to families formed after divorce and remarriage—step-parents and step-children and step-siblings pieced together in new patterns. The term can also encompass families that are interracial; in these families, blending takes on additional permutations that certainly have puzzled some throughout history.

Like other interracial families, those that are also blended through remarriage contend with external assumptions and judgments—the confused looks and questioning glances, the “ah-ha” moments or oblivious denial. When I was married to my daughter’s father—who, like me, has both a black and a white parent—I slipped into the ease of relative inconspicuousness for the first time in my life. Raised with my white mother, I had experienced the questions about whether I was adopted and had felt defensive about my own belonging. In my marriage, though, I was able to take for granted that others saw and accepted where I belonged. Releasing the guardedness I felt when I needed to defend my familial place, I nevertheless felt an alternative defensiveness that many “blended” families and people of color feel in mainly white communities.

Now that I’m divorced and partnered with a white man, I feel the return of my childhood alertness to others’ assumptions about my family. Blessedly, our society in general and our community in particular do seem to have come a long way since Loving v. Virginia, but none of us can believe that racism is eradicated or that interracial unions are always accepted with open arms and open minds. My partner and I have had only one obviously racist experience in our two years together, and thankfully it was subtle, but I don’t kid myself that the obvious incident we experienced was all we’ll ever encounter.

As we slowly blend our families, I’m watchful of additional experiences we might have—of hostile or benign racism—and how our children might be affected. Of course, I also must ask myself if my very watchfulness amplifies negative experiences or even turns neutral ones into negative. On one occasion when my partner took my daughter out for ice cream, a woman asked him if my daughter was his, noting his whiteness and her brownness. “Sadly, no,” he replied smiling, meaning that he would be proud to be her biological father in addition to feeling like a parent to her. The woman then proceeded to comment on how lovely my daughter looks, how “Indian.” Hmm.

I wonder, too, the experiences I might have on occasions when I’m with his twins, one of whom is a freckled, blue-eyed, red-headed beauty and the other an as-yet smaller version of his imposing father. Will people assume I’m a nanny? Hmm.

I wonder in which configurations we’ll have our familial status silently questioned or vocally challenged. When David is with my daughter, will his belonging somehow be allowed, if not assumed, due to his whiteness and maleness? Will my belonging be overlooked when I’m with his children because of my brown femaleness? And when the five of us are together, what will people see? What, if anything, will they say?

Ever the optimist, I’m hoping people will see a happy family, not unlike most other families, regardless of race or marital history. It’s a utopian vision, surely, but I also hope people will allow us to reflect back to them a certain level of social awareness, acceptance, growth. Blended families really aren’t such a novelty, and ultimately it’s that simple fact I hope people see.

Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.

Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.