Part III- Journey Back Home

From the time I was very young I can recall wanting to meet my dad. I would eagerly wait for postcards and letters from him filled with photos and talk of meeting each other. Sometime in elementary school all contact fell off and by the time I was in college I still had yet to meet him. I had this fantasy that once I met my dad and went to Turkiye to meet the rest of my family it would suddenly change my life and I would find the place where I’d finally fit in.

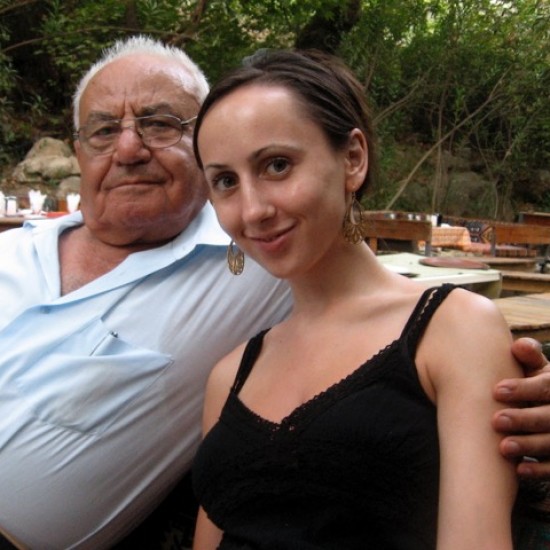

After years of waiting to contact my father I decided to try finding him via the internet through a search engine. Surprisingly, I found his contact information on a website about his art. I emailed him at first simply asking for my grandparents’ current address as I hadn’t communicated with my grandmother in many years. This eventually led to my visiting him a couple times in Florida. During one of these visits I met my aunt and uncle who were visiting. My aunt is not an emotional person by any account, but we both found ourselves crying when we had to part ways after just a few days of laughter, exchanges in broken English and Turkish and exchanging gifts. It would be a few more years before I would see her again.

One of the things that stands out the most to me about my visits to get to know my dad was how aware I became of my racial/ethnic identity when I was with him. Growing up in a white family as someone who can pass, race never really came up. However, when I would go out with my dad I was acutely aware that his phenotype and strong accent highlighted my difference to others. I can recall actually being frightened after 9-11 that people would attack us as many people make no differentiation between any of the countries or people in the Middle East, seeing them all as American enemies. In an odd way, despite my constant claiming and assertion of mixed identity- these were some of the first times when it was done for me. What was often an invisible identity to others became extremely visible in a way I did not have control over. To make things more complex being in my dad’s presence not only brought my race/ethnicity into question, but his accent brought our nationality and citizenship to the forefront. Despite all of my concerns, I cannot recall a circumstance in which I experienced anything negative due to race/nationality while with my dad, but this too is likely due to his racial ambiguity and being in multicultural areas.

As time quickly passed and my grandparents heard of my interactions with my dad, they had my cousins contact me and eventually get a trip setup to visit. After over 20 years of my grandmother ending letters with, “God willing (İnşallah) we will meet one day,” it was finally happening. For my mother and future husband this was not exactly the ideal time as the U.S. Embassy in Turkiye had recently been bombed, however I had this overwhelming sense of peace and confidence that this was where I was suppose to be at that exact time and there was no harm that would come my way.

I also knew that another chance may never present itself and was determined to go.

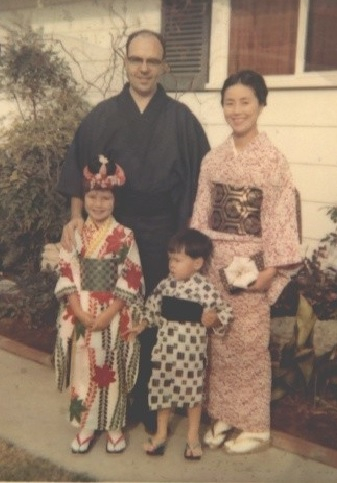

Funnily enough my biggest fear was getting lost in the airport and not being able to get help due to a language barrier and not recognizing my cousins who were coming to pick me up. My mom had also helped me practice what to say to customs agents about coming to visit family so as not to raise any suspicions given the recent political terrain. After all of my worrying not only did the customs agent not ask a single question, but everything in the aiport had an English translation and my cousins and I immediately recognized each other despite never having met and only one or two phone calls and a handful of photos. On the ride back to the Asian side of Turkiye I was surprised not only at how beautiful and surreal the country was, but that I was hearing American music on their airwaves.

I spent the next few weeks between Istanbul and Antalya. The country was as beautiful as I’d been told and my family collectively worked to make sure I met everyone and was treated wonderfully. One of my cousins used much of his vacation leave to spend time taking me around and we instantly bonded; it was as if we’d known each other forever. However, when I was not with my cousins, who could provide translation or when discussions would slip into Turkish or there appeared to be a disagreement of sorts I was reminded that I would never truly understand the family dynamics or feel that I one hundred percent fit-in no matter how hard they tried to make me feel included.

The most difficult part of the trip was spending a week with my grandparents and uncle where we were unable to communicate with each other. By this point I had finished the only book I’d brought, which ironically was Malcolm X’s biography detailing his trip to the MECCA, read every book in English that my family owned and written and recorded countless diary entries. My grandmother spoke to me in Turkish at a rapid speed with a smile on her face, while my grandfather took a silent approach by grabbing my hand and taking me along while pointing at things.

One of the memories I cherish the most was when my grandparents took me into town. We went into jewelry store after jewelry store where trays of gold were pulled out and they would look at me and point to the gold bracelets being displayed, while I would get extremely uncomfortable because I had no idea how much the jewelry cost. Finally we entered a store where one of the employees was able to translate and let me know that they wanted me to pick out a bracelet. I chose the smallest one. It had delicate circles that reminded me of the waves at the beach in Antalya. I watched as my grandfather pulled out what appeared to be an extremely large amount of money after they weighed the bracelet. My uncle and grandmother motioned for me to kiss my grandfather on the cheek as we walked out and as I did a very large grin spread across his face. Shortly after buying the bracelet my grandfather took a trolley back to the apartment and it was clear that his only purpose in coming along was to get me a special bracelet. When it was time for me to leave their home and return to stay with my aunt they each pulled a “typical” grandparent move, pulling me aside and “sneaking” me money.

The trip taught me two things. The first was that my family in Turkiye loves me simply because we are related; they don’t care if we speak the same language, live in the same country or have hardly spent any time together. They love me because I exist and nothing can stand in the way of that. I had heard about family being of extreme importance within Turkish culture, but experiencing it was quite another thing. The second lesson I learned was that at my core I am truly American and always will be. Even if I learn the Turkish language, spend every summer abroad and immerse myself in Turkish culture every second of the day I will still be the fringer within my family.

CONCLUSION

At the beginning of my journey I focused on finding an experience or place that would instantaneously make me feel one hundred percent understood and accepted at all times. I lived based on the premise that I was lacking something that I needed to find and only then would I be complete. What I found along the way was a series of confirmations that I am a life-long fringer and that my experiences and occupation of strange spaces—somewhere between Europe, Asia and America, between Christianity, Islam and spirituality, being a white passing Middle Eastern woman, yet identifying as mixed because I understand this experience more than my own culture— are what make me who I am.

One of the most powerful revelations I came to was at the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity a couple of years ago. After watching the documentary “A Lot Like You” I became very emotional and asked the biracial filmmaker Eli Kimaro if after traveling to Tanzania and shooting a documentary about her journey she has ever truly felt like she fit in with her Tanzanian family. Her response was profound. She told me that maybe our purpose isn’t to fit in. She gave an example of how she kept asking her aunts about their lives and cultural practices that she would have known never to ask about had she grown up in Tanzania, but through her outsider status she didn’t and persisted. Eventually her aunts opened up about being raped and brutalized. She told me that it was by her being an outsider that she unknowingly asked inappropriate questions, which ultimately resulted in her aunts finding some healing from what they had experienced. She then proceeded to tell me that her daughter has seemingly from birth had an innate and profound connection to Tanzania, so maybe that connection is not part of our purpose, yet our purpose of being fringers is just as important.

Now, instead of focusing on lacking knowledge and experiences I think about what I do know and who I can touch and connect with as a fringer. I understand a mother’s desperate love to protect a child from a culture she did not understand how to navigate, so somewhere in a synergy of love and fear she did her best, which meant distancing the child from the rest of her family and identity. I know what it’s like to “reclaim” your name and heritage and find a parent using Google. I know what it’s like to be raised by a biological parent, yet take the journey of a transnational/transracial adoptee to find their biological family members only to realize how much you are like them, yet how you are so completely shaped by the family that raised you. I know what it’s like to take a life-changing journey that is simply a beautiful exotic extended vacation to those around you, meant to be discussed for a week or so upon return before being shut away in photo books to be discussed on a rare occasion. I know what it’s like to be an adult in academia and still get that feeling of discomfort when asked how I identify or worse yet, have my identity policed by others. Most of all I know that the validation and acceptance I flew thousands of miles to find was never something anyone else could provide. That’s the ironic thing about journeys, we frequently come to the realization that what we believed to be lacking and searched for externally, has in fact always resided within the core of who we are patiently waiting to be realized.

Naliyah Kaya is the Coordinator for Multiracial & Multicultural Student Involvement & Community Advocacy at the University of Maryland College Park where she works closely with Multiracial/Multiethnic and Native American Indian/Indigenous student groups, serving as an advocate for the needs of these communities. She currently teaches TOTUS Spoken Word Experience and Leadership & Intersecting Identities: Stories of the MULTI racial/ethnic/cultural Experience.

Naliyah Kaya is the Coordinator for Multiracial & Multicultural Student Involvement & Community Advocacy at the University of Maryland College Park where she works closely with Multiracial/Multiethnic and Native American Indian/Indigenous student groups, serving as an advocate for the needs of these communities. She currently teaches TOTUS Spoken Word Experience and Leadership & Intersecting Identities: Stories of the MULTI racial/ethnic/cultural Experience.

As a poetic public sociologist, Naliyah utilizes poetry as a medium for teaching and social change. She encourages students to engage in artistic expression as they examine their own identities, beliefs and values and as a form of activism in promoting social justice. It is her hope that through this process of self-exploration students will embrace cultural pluralism, find commonalities across differences and engage in research and dialogues that seek to benefit the greater good of society through positive social action.

A native of Washington State, Naliyah grew up just outside of Seattle. She earned an A.A.S. from Shoreline Community College, a B.A. in Sociology from Hampton University, and received her M.A. & Ph.D. in Sociology at George Mason University. Her poetry has been published in Hampton University’s literary magazine The Saracen, George Mason University’s Volition, Voices of the Future Presented by Etan Thomas and Spindrift Art & Literary Journal.

Learn more about Naliyah and her work on her website.