I’ve never really liked Christmas. It was the most forced family event of the year, defined by spectacular displays of anxiety from my mother and bad temper served up by my father, always in time for guests. While that doesn’t sound much different from others’ fun family holidays, there was another layer of dysfunction in it for me. My Dad is Muslim, a fact that we ignored for the entire year, not just on big Christian holidays. December 25th highlighted particularly well the lack of Muslim traditions in my immediate family, despite the fact that Lebanese Muslims outnumbered my English mother’s kin and me and my American siblings.

Let me walk you through a typical Itani Christmas (you Arabic speakers know how ridiculous the pairing of a large Lebanese Muslim family name and the word “Christmas” is). In the morning, my siblings and I woke up way too early and tore into our presents like obnoxious kids the world over. The gifts broke along gender and culture lines. As the one with the Arabic name and the insatiable curiosity for all things Middle Eastern, I would get the “cultural” gift (a subscription to Foreign Affairs was popular). “You’re so…Oriental,” my mother would often say, perplexed, in her British accent. Um, yeah Mom, did you see the Lebanese guy you married? Just saying.

My brother Stuart would get the “sports” gift, although all of us were athletic. And my little sister Fiona, the most American of us all, would get the “American” gift, usually trendy clothes and music that made me seethe with jealousy (apparently a cross cultural trait).

Before we had a chance to take inventory, my father was barking orders to clean up wrapping paper, salvage gift cards, and organize, organize, organize. It was like he was auditioning for the Captain’s role in the Sound of Music. Soon after presents, we piled in the car and drove to a nearby park to take the dogs for a walk, usually in a few feet of snow (Ohio. Enough said). Dad had all people and canines walking at a brisk pace, making the activity feel more like surgery prep in his hospital OR than fun in winter wonderland. Again, Christopher Plummer’s Austrian captain comes to mind.

Meanwhile, my mother was busy doing her own prep in the kitchen. The turkey—the crowning glory of an English Christmas dinner—was brined, dressed, and popped in the oven. The Brussels sprouts were chopped, the potatoes scrubbed. The best dishes were laid out, ready to display and serve the meat, overcooked vegetables, and Christmas puddings that had come all the way from Harrods. With amazement, we watched her recreate the Christmases of her childhood in post-war Britain.

But then came the Middle Eastern part of Christmas—hummus, baba ghanoush, tabouleh, lamb kabobs, and honey and nut-ladened sweets. You see, our Christmas always included the Lebanese dishes that we grew up on, the ones that my father taught my mother to cook for him when they were residents in London. It was delicious, and pure torture. Mom worried for days about the food and the guests. She became almost crippled at the thought of my father’s temper if things weren’t perfect. The food was always amazing, but my mother never seemed to enjoy it. While Dad entertained guests with awkward conversation, my mother usually sat in silence and the kids skulked off, not sure what to do.

No matter what kind of crazy family shit went down on Christmas Day, we came together around a feast of traditional English food and Lebanese dishes. Seriously, mezze and Christmas turkey…the best. Food got me through the uncomfortable reality that each year, we celebrated Christmas and ignored Ramadan. I didn’t know when Ramadan started, or how to properly break the fast at sundown. I didn’t know the customs around Eid al Fitr or Eid al Adha. But I learned all about Christmas, little baby Jesus, the three wise men, away in a manger. My Dad loved parts of Christmas like having a tree with lights, but kept his Muslim traditions private and shared nothing with his wife and children. The reasons ranged from laziness to bigotry. There was the subtle and overt racism—comments, knowing jokes, workplace reviews—that he faced while pursuing a surgery career in the US and the UK. And without a Muslim wife to educate the kids or a mosque to attend, it was easier to keep to himself and find a secular middle ground complete with Christmas trees and Easter chocolate.

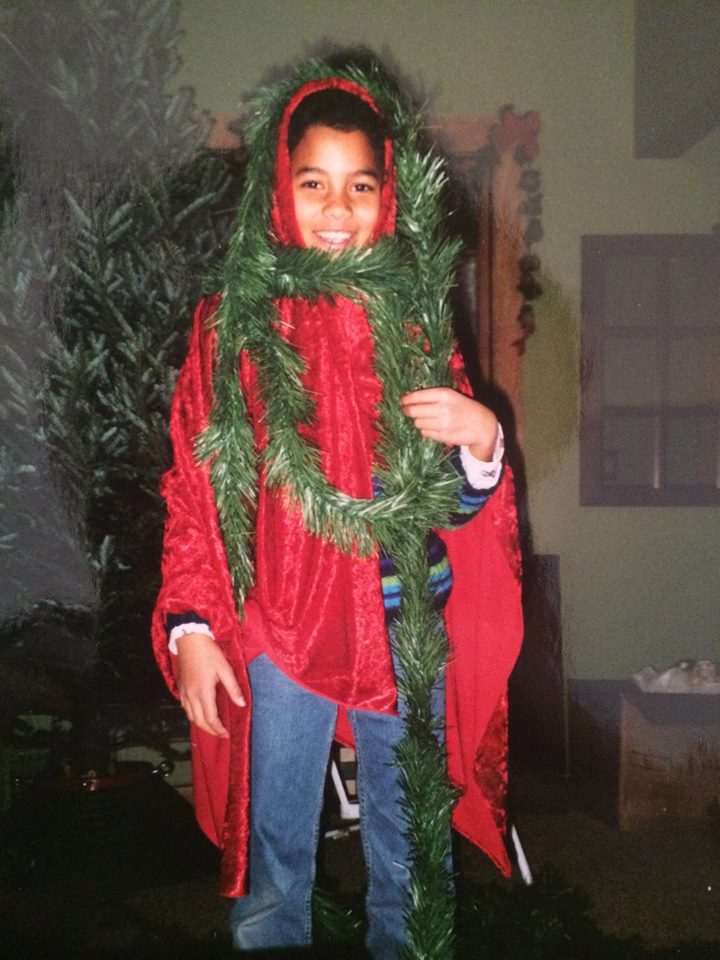

As the kid with the Arabic name and the stubborn nature, I pushed away my mother’s holidays in response to the absence of my father’s Islam. I saw Christmas as a farce that hid my parent’s unease with each others’ religions. Seriously, how can you have one holiday without acknowledging the others? How can you only know about one half of your family? How can you have Christmas without Ramadan? I downplay Christmas every year because I feel like what’s the point? It’s only half of my story. I get frustrated. I’m scared that if I focus too much on one side, I will lose the other.

Many of us whose families span religions and nationalities cut corners to keep the peace, or make sense of things. We abbreviate religious traditions and holidays, and rely on food to help us come together and show love, even when it is confusing or incomplete. Don’t get me wrong, the cultural fusion that marks so many of our communities is vital—and delicious. But when Christmas rolls around each year, I have trouble getting excited ripping into the wrapping paper, going to “holiday” parties, or even having a tree. I am still trying to find the balance for myself. But having hummus with the holiday turkey, or baklava with my Christmas cookies? Not a problem.

By Zena F. Itani

[rescue_column size=”one-fourth” position=”first”] [/rescue_column]Zena Itani is an Arab American activist, athlete, and adventurer. She is a public health practitioner with over a decade of experience building innovative organizations and programs, and using multimedia for planning, storytelling, and advocacy. A resident of Washington, DC, Zena now lives in Amman, Jordan with her family. You can find her in her garden in Jabal Amman and on Twitter at @ZenaItani.

[/rescue_column]Zena Itani is an Arab American activist, athlete, and adventurer. She is a public health practitioner with over a decade of experience building innovative organizations and programs, and using multimedia for planning, storytelling, and advocacy. A resident of Washington, DC, Zena now lives in Amman, Jordan with her family. You can find her in her garden in Jabal Amman and on Twitter at @ZenaItani.