The idea behind a shared lived experience is that different people can identify with similar things that happen as a result of some part of their identity. Unfortunately, I have met too many people who don’t understand or accept that the mixed experience is on equal footing with any monoracial experience. I’ve listed five common experiences that I have noticed as a black and white biracial woman, but that apply to other mixed backgrounds, as well.

- Explain, Justify, Defend

Multiracial people are very familiar with constantly having to explain, justify, or defend who we are, our experience, and essentially our existence in the world. The most obvious example of this is the question that all mixed or racially ambiguous people know well: “What are you?” However, the issue goes much deeper than an inconvenience or awkward conversation starter. Sometimes, the answer to the question doesn’t satisfy the asker. It may lead to further explanation or in rare cases, even to an argument.

I am often mistaken for Afro-Latina. More than once, when a Latino person has asked me what I am and I respond, they can’t believe my answer so they continue questioning me. “Really? You have no Latina background at all? But you have the face of a Brazilian. (I don’t know what the ‘face of a Brazilian’ looks like, but it has been said to me.) And you dance salsa? You must have at least some Latina in you.” In this situation, my reaction may be amusement, annoyance, or simply boredom with the conversation. In situations involving monoracial black people, things can go a different direction. The dialogue can get much more heated and emotional due to a perceived betrayal or rejection of blackness. In my experience, any negative reaction is more commonly a subtle change in tone of voice or mood. I have a visceral reaction, as well, because I know this to be far from the truth and am hurt by the questioning of my right to accept myself as a complete human being and acknowledge my lived experience.

I often avoid these conversations entirely because even the most subtle slights become exhausting and the conversation has never resulted in increased understanding or even acceptance of my experience. Despite what some have been made to believe, acknowledging and validating different experiences among people of color does not create division; rejecting them does.

- Rejection

No one likes rejection, but everyone experiences it at some point. For mixed roots people, rejection can come from one or all sides of one’s heritage at different times. This reality is what leads to the common feeling of being an outsider and not knowing where we fit in in a racialized world.

Some multiracial people, myself included, are most comfortable in racially diverse environments because there is less pressure to conform to the group along racial lines. There is a certain trauma that comes with being rejected over and over again. After years of rejection based on race, you develop defense mechanisms and learn to avoid situations where rejection is more likely, such as a monoracial group setting. But when that avoidance happens, it can be seen as thinking you’re better or rejecting the race. Since we are rarely given a space to talk about mixed experiences, resentment and misunderstanding continue unaddressed.

- Acceptance — With Conditions

The other side of rejection–acceptance–still involves rejection in a way. Acceptance into a monoracial group often is contingent upon mixed people subverting their own unique experiences as mixed people. If you mention your mixed experience, you risk having to justify or defend it. (See #1) But if you never speak of your experience of being mixed, unless it’s to acknowledge light skin privilege, then you are acceptable. Again, I tend to keep those experiences private because I don’t want to be put in a position where I feel compelled to defend my lived experience.

Groups want to claim or reject multiracial people whenever it is convenient- to some people I am black, period. To others, if someone has a parent of any race other than their own, they’re not truly a member of that person’s race. To some white people, as long as you’re some shade of brown or ethnic looking, you’re a minority and that may be enough information for them. At least in my case, I’m sometimes treated as an honorary Latina because I can pass for Latina, I speak Spanish, and dance salsa. All of this can be confusing, especially for youth, and it is why I believe it’s incredibly important for mixed race people to have a strong sense of self despite what anyone else decides to project onto them.

- Fluidity

Fluidity, when it comes to the mixed experience, means the ability to move between different racial categories and having a variety of experiences with and entry points into different cultures. This wide experience can provide deeper insight into race and the way it plays out. It also means that your perceived and internally felt identity can change depending on your environment. While this is a privilege because it allows increased access to a variety of spaces, there are also downsides. In a world where everyone wants to put people in a box, fluidity can be confusing and very isolating. There is a particular kind of certainty and solidarity that comes with a singular racial identity, something multiracial people do not inherently have. As convenient as it can be to blend in with multiple crowds, it is human nature to desire and seek out one stable community that feels like home.

- Letting Things Slide Off Your Back

The term “microaggressions” has gotten more attention lately due to the increased dialogue around race. Multiracial people experience microaggressions just like any other minority group; some that are shared with monoracial groups and some that are specific to multiracial people. The difference is microaggressions come from all of the races to which we belong. Sometimes I feel on edge, ready to brace for the impact of microaggressions or outright aggressions from either side. A simple, dismissive “oh, but you’re light-skinned” can throw someone off balance regardless of the intention behind the statement. On top of that, multiracial people are not supposed to speak of the unique experiences they encounter. As I mentioned before, speaking one’s own truth can somehow be seen as a betrayal or statement of superiority.

~~~

None of this is to complain about being mixed race; there are ups and downs to everyone’s experience and I am not a fan of the Oppression Olympics. However, I do believe there needs to be more listening and understanding of the fact that our experience as mixed race individuals is no more or less valid than anyone else’s. It is my hope that one day this fact will not need to be stated because it will be implicitly known.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

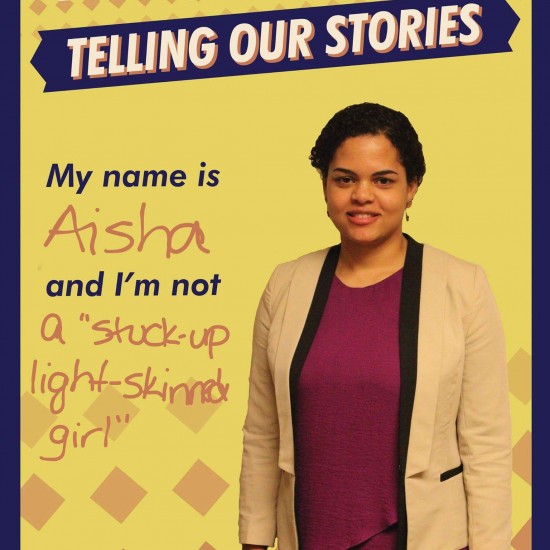

Aisha Springer is based in Baltimore. Her writing primarily focuses on issues of race, feminism, and personal essay. She is a Contributing Writer for Hashtag Feminism, a blog examining feminist topics through a media lens, has written book reviews for STAND, the ACLU magazine, and was a 2015 Social Good Summit Blogger Fellow for the United Nations Association (UNA-USA). During the day, she works full-time at a civil rights nonprofit.

Aisha Springer is based in Baltimore. Her writing primarily focuses on issues of race, feminism, and personal essay. She is a Contributing Writer for Hashtag Feminism, a blog examining feminist topics through a media lens, has written book reviews for STAND, the ACLU magazine, and was a 2015 Social Good Summit Blogger Fellow for the United Nations Association (UNA-USA). During the day, she works full-time at a civil rights nonprofit.

Aisha has a Master of Public Administration from American University and a B.A. in Spanish and International Affairs from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.