As a student of jazz at my university, I often occupy white male dominated spaces. I am the only woman of color (a black/white biracial woman) in a jazz history class, “Jazz Musicians as Composers,” a course that explores the gray areas of jazz as a concert music. Sometimes, I wonder if I can give myself permission to be a woman of color in this space. In a discussion surrounding the “Freedom Now Suite,” Max Roach’s response to the Greensboro sit ins, I have 75 minutes to say something—anything— so that my professor doesn’t think that I’m “just a shy student.” Rather, I negotiate with myself for 75 minutes what I am allowed to say, how what I say is a reflection of the body I occupy. Pressure mounts as someone questions the rigidity of jazz as a “black” art form. Pressure mounts as students discuss the auto-exoticism of African-American jazz musicians. Pressure mounts as the professor asks if anyone has ever felt that they had to represent a group of people, to act as a monolith. I scream silently: “Yes, every time I enter your class. Every time, for 75 minutes, I measure the amount of voice and the amount of blackness that I allow myself to have.”

What does my body mean here?

. . . . .

Liminality.

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

audre lorde, a litany for survival

Liminality is vast, infinite. There are no impossibilities. In liminality, there is enough room to breathe.

Liminality is the top of the breath. It is filling your lungs, oxygen massaging their pink lining, brushing into corners that you didn’t know existed, air pressing into ribs. You could fill your lungs forever, but you don’t—for convention’s sake.

Liminality is the asymptote. It’s the space between two curves closing in on an axis. No matter how far it travels, it can never touch zero: a value that is both a number and the absence of a number. Zero, the asymptote, is both/and.

Despite its confines, there is room to breathe in liminality. But in this infinite space, never-ending combinations and intersections can also feel like limitations—boundaries defining what you are not. These intersections, azure lines on graph paper, can box us in until this liminal space feels suffocating. Sometimes in intersections, there is no room to breathe between these walls.

After the end of World War II, Germany—a battered and broken nation—was left to the political players still standing. In this time of post-war wreckage, Great Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union divided the land into East and West Germany. The capital, Berlin, too, was subject to division despite its physical location in East Germany under Soviet occupation and thus became two halves: East Berlin, under the eyes of Soviet soldiers, and West Berlin, within the hands of American, British, and French troops. In 1961, the Berlin wall began to take shape.

West Berlin became a dim light in darkness as the Soviet’s occupation on the other side of the wall resulted in poor treatment of its citizens. As East Berliners sought freedom by “illegally” crossing into West Berlin, the wall became a sight of loss and memorial for those killed in their attempts. Eventually, to increase security, the Berlin wall transformed into a multi-layered structure: between two walls fortified with barbed wire existed a no man’s land in which guards would shoot wall hoppers. Between these walls lived a space with no definition: a space that was neither West Berlin nor East Berlin. No one lived between these walls: the lucky ones moved between, across, in transition while guards did death’s work… until their shifts ended. How could any identity exist without life in the space between these walls? Who are you “in doorways coming and going / in the hours between dawns?” Are you a transition?

. . . . .

Bridge.

1,950 mile-long open would

dividing a pueblo, a culture,

running down the length of my body,

stalking fence rods in my flesh,

splits me splits me

me raja me raja

…Yo soy un puente tendido…

“I am a bridge,” writes Gloria Anzaldúa, voice of intersections. In Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, she describes how her body—its mass, its fullness, its veins pumping blood—connects cultures, languages, people. I imagine her soft, naked skin sprawled across 2,000 miles of desert borderlands. Her body, nearly 2,000 miles long, lays down as her calves, back, shoulders rise hundreds of feet in altitude. I imagine small people sinking their fingers into her soft skin, gliding across her back. Into Anzaldúa, the border disappears. Whatever wall existed melts beneath her breasts and under her breath. Her skin, a skin made for this desert, connects space.

The mestiza, mulatta, her body becomes a bridge. In her body, she adapts, translates, code switches. She becomes the bridge upon which others—the less adaptable, the more comfortable—walk, small steps on plush skin.

Robert Park’s Marginal Man Theory positions a biracial person “outside of the two races to which he belongs, a stranger in both worlds. His personality to the development is based on how he adjusts to the crisis, which is a permanent crisis because he is socially located between two irreconcilable races” (Rockquemore 36).

A stranger in both worlds. Not a bridge but an outsider “socially located between two irreconcilable races.” Anzaldúa and Park offer contrasting positions: she connects and he excludes. She reconciles and he dissociates. She constructs a bridge across two walls and he lives between them. Both are unnatural.

“A Borderlands is a vague and undetermined place,” writes Anzaldua, “created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition” (Anzaldua 25). Where do connection and isolation meet? Are you a bridge?

. . . . .

Fullness.

Like a glass of water, you fill it till its whole. Full. Completely adequate.

“What are you?” Nine times out of ten, I respond with: “I’m half black and half white.” It’s easy, it’s true (more or less), and it’s habit. But speaking in fractions is a dangerous territory, risking a sense of incompletion, insufficiency, fragmentation that I might impart upon the person who asked. Two halves and twice as incomplete. Now how is that possible?

Most days I wake up full. My body contains no gaps—I fill my lungs until infinity. I have a full body.

I step out of bed and walk to the bathroom. I turn on the light and greet myself in the mirror. On some days, the gaps appear. My hair seems to resemble that of my straight-haired friends, with a just few more coils and frizz. When did that happen? I look for my mother in my face… then I give up. What am I missing? Fluorescent lights make my skin look pale. I wonder: Maybe I do need more sun.

On these days, the gaps eventually fill in. I hope not to feel them tomorrow.

Biracial: two races. Biracial: a binary. Biracial: one body between walls, across borders, in vast liminality.

. . . . .

I sit at my desk. My breath is still. I inhale slowly, feeling my ribs expand, my back pressing into the chair. I fill my lungs until somewhere, the top of my breath—the minuscule space of stillness between inhale and exhale—turns into a release. I raise my hand and speak.

Works Cited

Anzaldua, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

Lorde, Audre. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997. Print.

Rockquemore, Kerry, and David L. Brunsma. Beyond Black: Biracial Identity in America. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littelfield, 2008. Print.

Carly Bates is an artist emerging from Phoenix, Arizona. With a background as a pianist and vocalist, she is active in the Arizona arts community as a creative collaborator with musicians, dancers, poets: storytellers. Carly is pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Music and a minor in English Literature from Arizona State University. Towards earning her degree, she is one of three women using the body, voice, and narrative who wrestle with questions of heritage, disbelonging, and specifically her identity as a mixed race woman in a performance titled Negotiations.

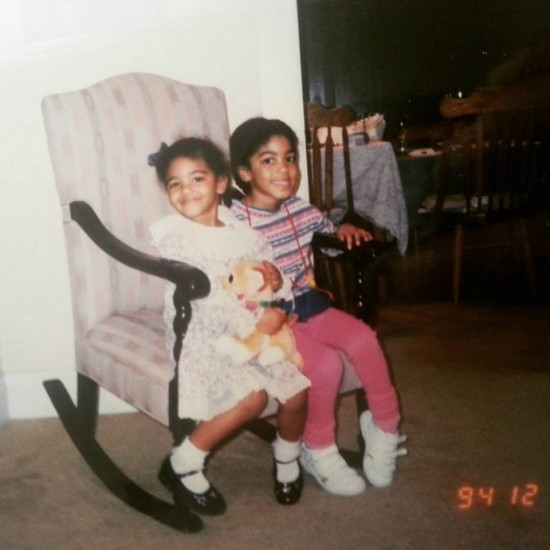

[Photo by: Bethany Brown]

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.