I’m a slice of marble bread

surrounded by white loaves,

captive in a Baker’s rack,

waiting to be displayed

in the storefront counter.

“Whiteness” in the appetite of man eludes and, at times, overwhelms me. Embedded in every conceivable medium, archived for posterity, true or not. Its myths secure,

legends immortalized,

legacies glorified.

What about the rye and pumpernickel among us? Does not our past, our presence, deserve a place at the banquet table?

By omission, we have gone missing.

Null and void.

Abandoned to maintain

a color coded status-quo.

What is to be gained and lost

in willful exclusion?

All people work and play,

give and take,

rejoice and weep,

sacrifice and endure.

All people are resolute

in their beliefs and fall victim

to an assortment of weakness.

All people,

beautiful and plain,

bleed.

Empathy, not indifference

defines our humanity.

Why intentionally

remove and render moot

the embodiment and deeds of others?

Unless one fears truth of message, assimilation of cultures–Or, moreover, the fear of a new reality, that of a changing demographic, of equal footing and competition for land, home, position, influence and power.

Within the contiguous U.S. borders

and pallid

empowered culture,

we don’t exist.

We’re invisible, expendable.

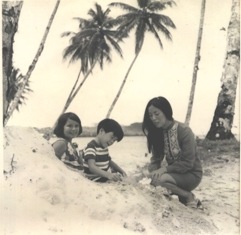

Our story,

Our family history

hasn’t been told,

truthfully.

As people of color,

we’re marginalized, mere footnotes

in the American storyline,

bereft of accomplishment,

alien, irrelevant and insignificant,

reduced to contrived,

“other than white” census boxes.

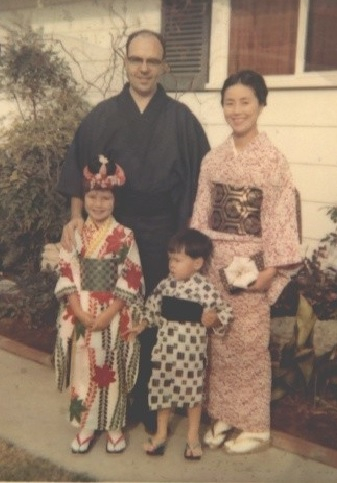

My story is much like yours, only different. Our narratives simultaneously coexist under dissimilar conditions. Our lives are both analogous and divergent, but interchangeable without invalidating the other.

The duality of American life;

confounding, yet discernible.

The irony, of course,

is that we’re just breads

of different colors,

braided and rolled together.

More palatable

if baked

into dense textures,

flavors enriched

when served warmly.

Man, like bread, takes time - to rise to the occasion, in need of a leavening agent to ascend.

Bakers know how to make yeast grow and dough to expand. When exposed to extreme temperature, the yeast will die, the dough will never rise.

Man, too, needs no less

an agent for change;

an accepting social temperature

and environment

to grow and fully develop.

Personally, I like all kinds of bread:

light rye, dark rye, pumpernickel,

marble, flat-breads, sourdough,

even plain old “white bread.”

The make of bread borne of the oven

is not in question,

– the Baker is,

and bears a name.

It’s you. And it’s me.

It’s plainly evident

by the powdered residue

on our hands.

How about we share some space

in the kitchen

and while we’re at it,

a little history?

Manipulation of the past is an amplified device. It serves a purposeful conveyance–to increase the volume and channel voice in one direction; to sanction or moderate people and events.

It deliberately lacks

honest perspective and clarity;

and is much too often

uncharitable to the deserving.

If we choose to, we can change all of that.

All it takes is a slightly modified mixture of flours, some yeast and water, tender but thorough kneading,

a hospitable temperature, and most importantly– consciousness–to provide all of us with the truth

and the sustenance of worthiness.

Frederico Wilson is currently the owner and President of an International Fluid Power Procurement and Sourcinwg Company; founder of a non-profit organization (under development); blogger at mestizoblog.com, focusing on multicultural perspectives and issues. He is a USAF veteran (environmental/missile inspection specialist); and former domestic and international professional in the Airline, Telecommunications, Sales, and Financial Securities industries. Originally from Arizona, he is a lifetime student of cultural anthropology and applied behavioral science. He attended Arizona Western and the University of Arizona and holds numerous military technical, and corporate management certifications and licenses.

Frederico Wilson is currently the owner and President of an International Fluid Power Procurement and Sourcinwg Company; founder of a non-profit organization (under development); blogger at mestizoblog.com, focusing on multicultural perspectives and issues. He is a USAF veteran (environmental/missile inspection specialist); and former domestic and international professional in the Airline, Telecommunications, Sales, and Financial Securities industries. Originally from Arizona, he is a lifetime student of cultural anthropology and applied behavioral science. He attended Arizona Western and the University of Arizona and holds numerous military technical, and corporate management certifications and licenses.

He is of mixed Mexican, Indian (Yaqui Tribe), Euro-Iberian, and Cornish Celtic ancestry. He lives, works, and writes in metropolitan Seattle, Washington.

He is best described by a quote attributed to Anthony Bourdain when recounting the preparation of a Burgundy wine-base rooster entrée.

“So, they take this big, tough, nasty-ass rooster, too old to grill, too tough to roast. Marinate and simmer the shit out of it, before it’s tasty.”

Frederico is the author of a new book, Escaping Culture: Finding your place in the world. Find out more on his website: mestizoblog.com