Sometimes I laugh at the impossibility of my experiences. I find humor in the challenges and privileges that shape the way that I uniquely carry myself in this world. I used to shy away from being special, now I own it before I let others try to own me. It has been a long process of coming to terms with my true self and exploring my identity, my roots, the blood that has made me and yet, now I find it so incredibly easy.

Thanks to love from some of my elders, mentors/femtors and a lot of prayer and time in nature, I breathe my truth without permission and find power in my occasional loneliness.

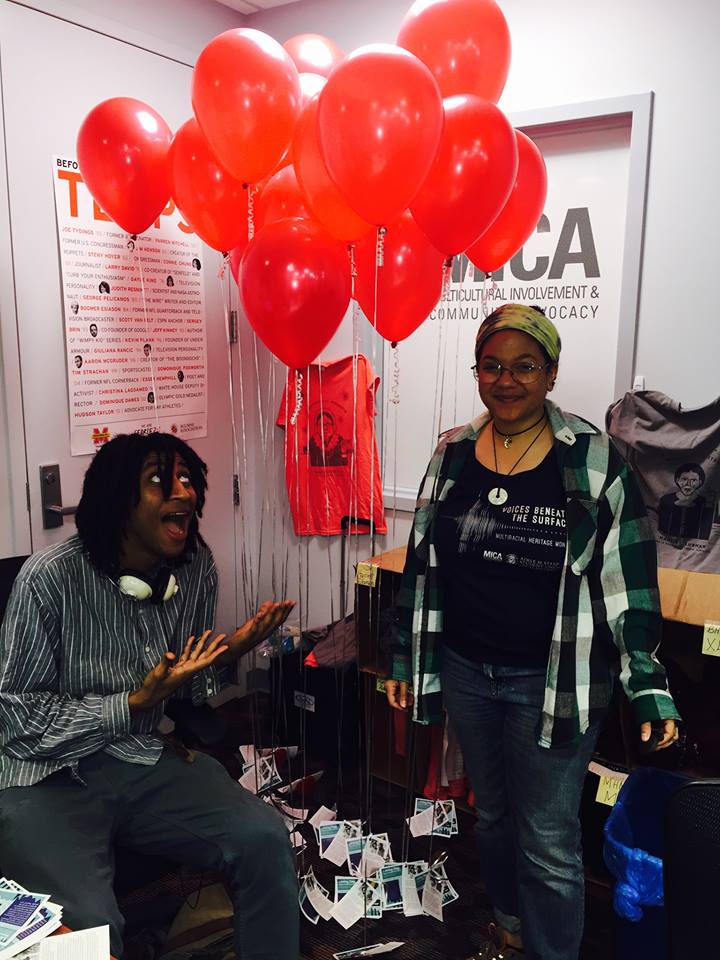

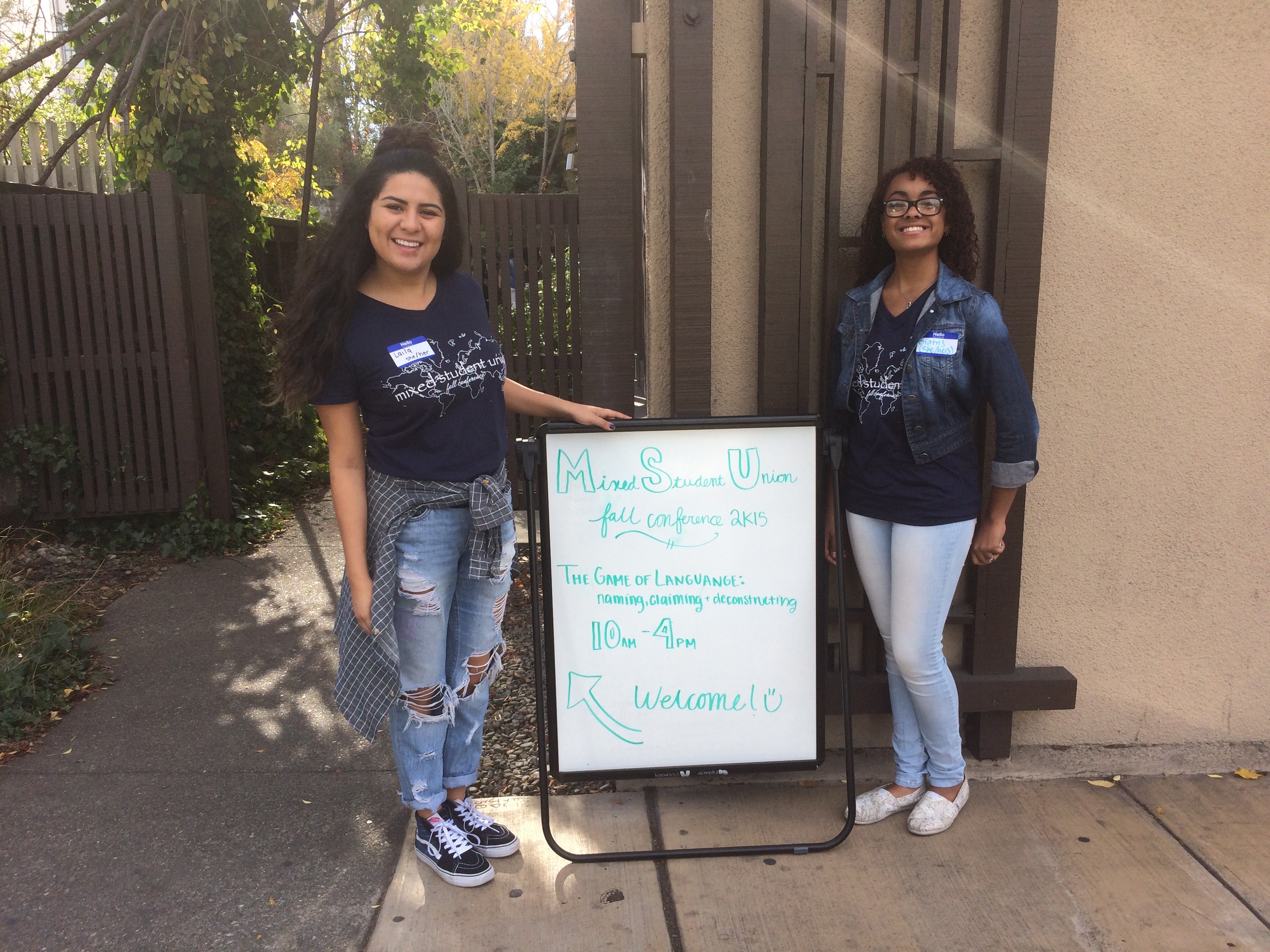

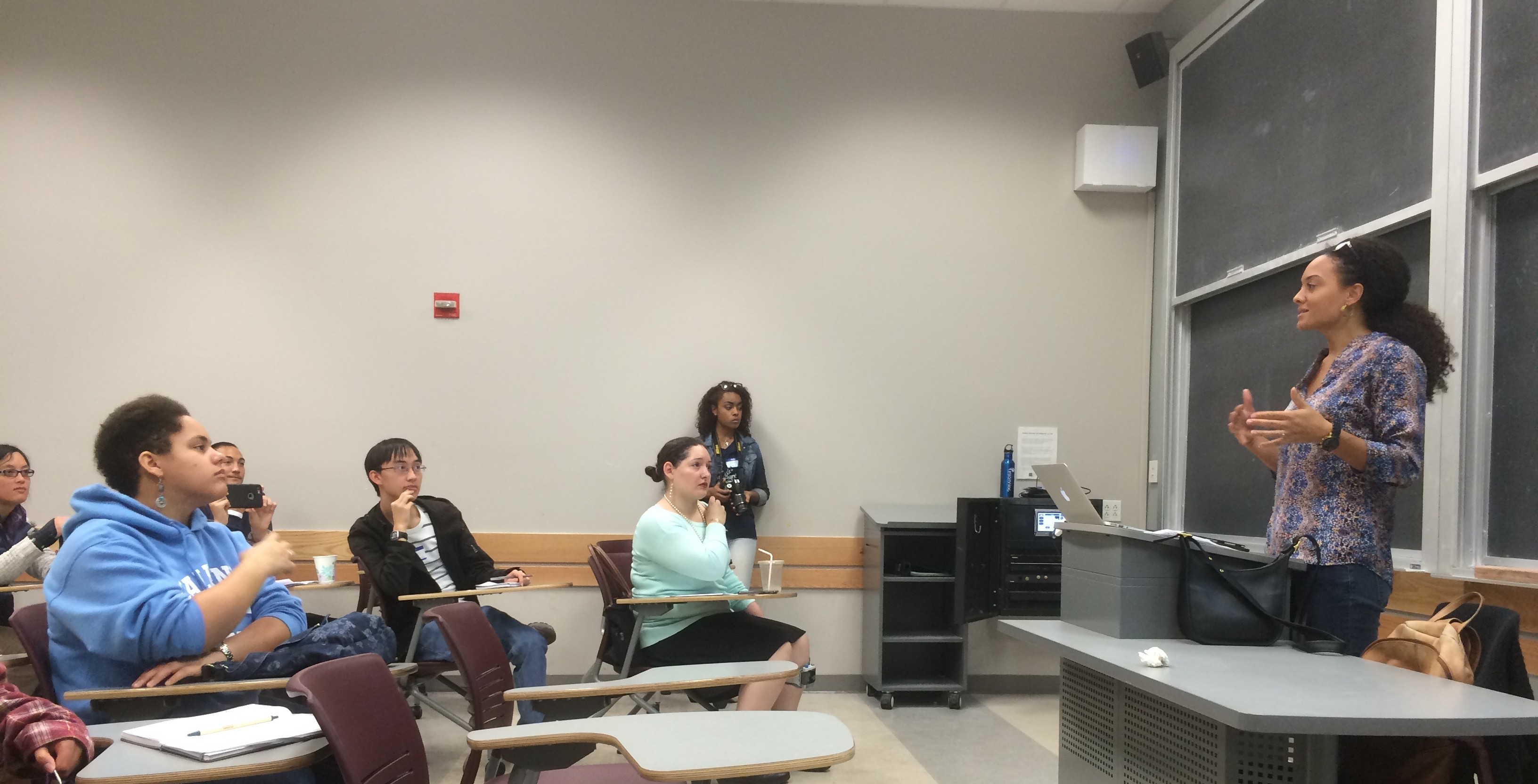

This Saturday was the 4th Annual Mixed Heritage Conference at UCLA sponsored by the Mixed Student Union at UCLA. For mixed folks, conferences like these and organizations like MSU are like coming home for the first time, like the opportunity to be reborn, like being hugged in a new way. Like any community, being seen, heard, felt, and recognized by folks that identify the way you do is essential for survival. I have not been in a conscious and intentionally mixed heritage space in over a year. Sure, I have hung out with my mixed friends and have talked about the issues facing the community, but the formal recognition of our lives and the sharing of space dedicated to mixedness is powerful blessing all on its own.

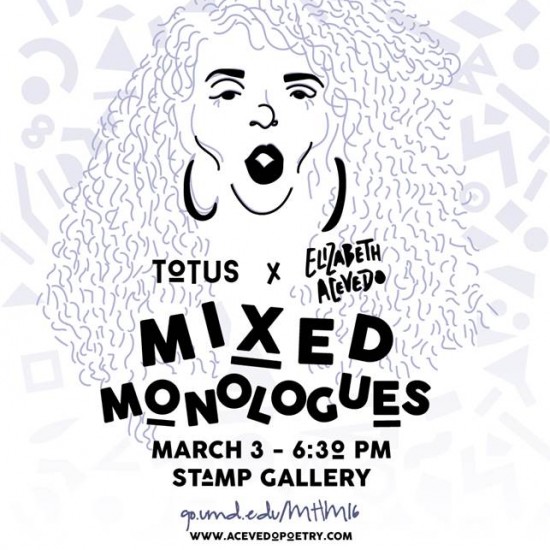

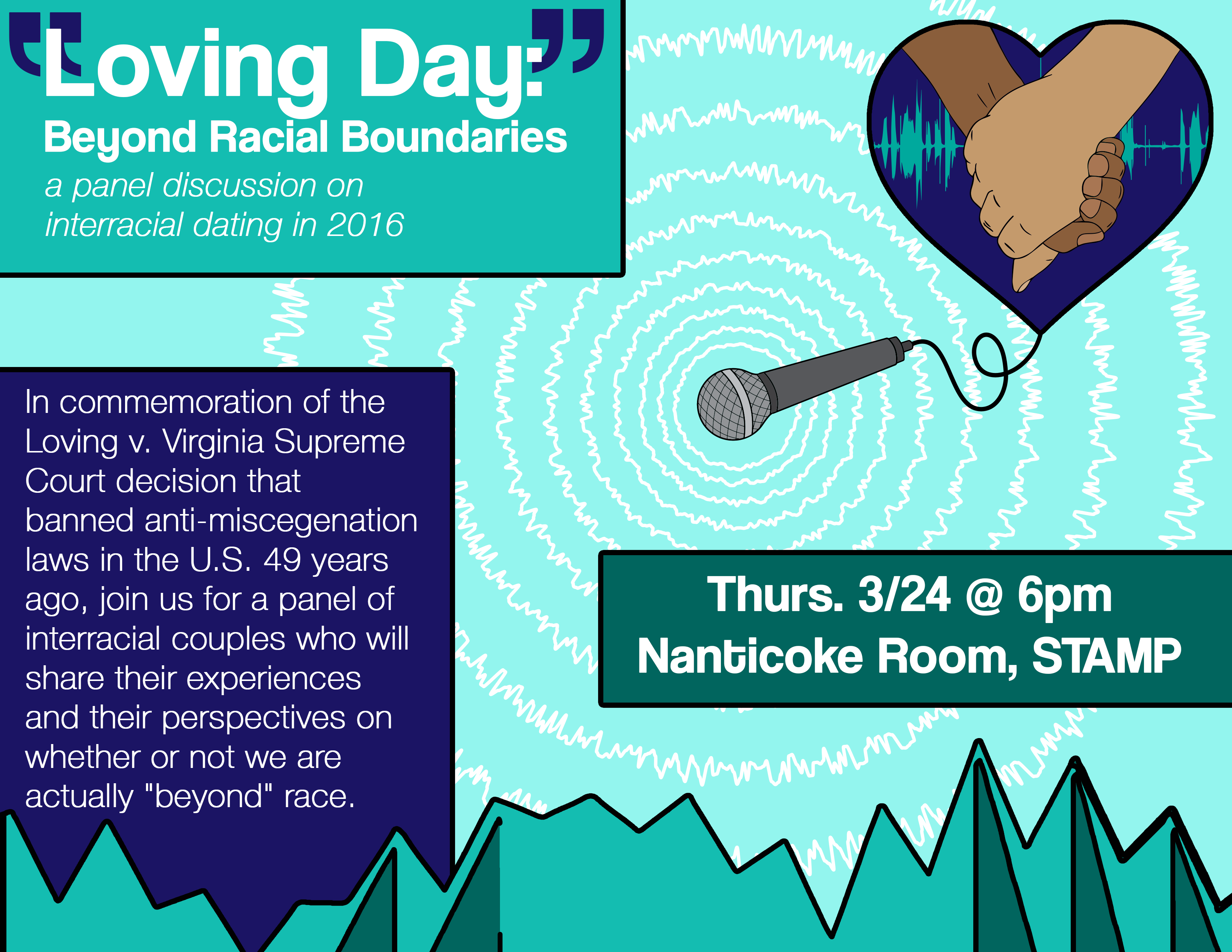

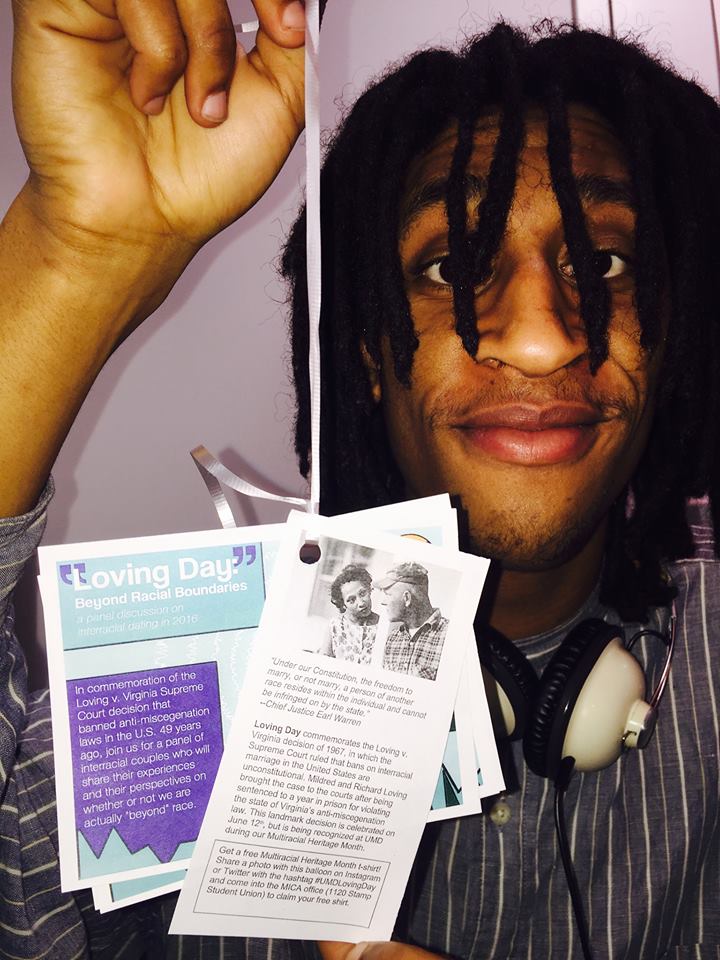

I cried twice during the conference. The first time was out of being completely overwhelmed. I co-founded MSU at UCLA with my friend Tara Sweatt in the fall of 2010. We were two people. Two second year multiethnic women of color Bruins that were determined to feel safe, to advocate and to carve space into UCLA for mixed folks. We dedicated 2 full years at UCLA to getting this organization off the ground. We built a team, we made flyers, we developed a mission, and we got to talking. We talked a whole lot. We answered over a million questions, most of them were one of three common questions on a loop: “What is mixed?” “What do you do?” “Why do you exist?”… Soon enough we had a banner, a mailing list, regular meetings and slowly made a name for ourselves. We met at night, on weekends, texted during class and exhausted on campus and off campus resources. We defended our right to exist, explained more than we expressed and put on events attended by over hundred people. Art gallery shows, panel discussions, workshops with youth, and social outings became our lives. We were adamant, unrelenting in our messaging and fearless with our intentions. We had stories that we needed to be heard, we wanted to be there for one another, we wanted to put context to mixedness historically in order to politicize mixed folks on our campus.

It was a labor of love and sacrifice. It had never been done the way that were doing it. We shook the status quo, changed the game of campus even if only a tiny bit, and linked our struggles to other communities. We built it, and people showed up. Six years years later, a generation of new leaders that do not even know our (the founders) names, are fiercely upholding the legacy in their own way and paving new conversations on campus.

I cried at the beauty of the legacy. I cried at the perpetual fatigue I had experienced that was finally catching up to me from having to defend our right to exist on campus and explain our unique experiences as mixed people. I cried for the amazing students I mentored who have since graduated, I cried for the realization of the vision we had 6 years ago. I cried that we had been an organization long enough to apply for permanent office space on campus. I cried for all the incoming mixed Bruins who did not have to search too far for their first home at school. I cried at the fact that we are still claiming space in a political way. I cried because I was overwhelmed that a conversation that I had with my brother on a late Thursday night in the living room of the one bedroom L.A. apartment that we grew up in, actually turned into an organization and now is a force to be reckoned with. From a conversation, to a dialogue, to a space, to a presence, to a MOVEMENT. TEARS. I cried because this last year has been the worst year for me in terms of stepping out of anger and letting go of family members that foster racism in my proximity. MSU is the only space I can imagine that could help me heal in spirit, even if from afar and through memories. Half a day at this conference and I already feel more human in the midst of familial racism placed to tear me up. “M-S-U”sounded so new before, we would repeat it so often to convince ourselves that we were real. Now the letters sound confident in themselves, whole, grounded, based in 6 years of hard work and community building.

The second time I cried was because the closing performance of the conference held truths that I could so closely relate to. Fanshen Cox’s “One Drop of Love” performance piece was so personal and relevant to my experiences that I cried of relief. It can be shocking to feel camaraderie with other people when mixedness can very often feel like an island. So often amazing, but an island nonetheless. To watch Cox’s calm as she settled into her performance for an audience that she knew she didn’t have to explain a whole lot to was inspiring. Relief is the only way I can think to describe it. The laughter that her performance ignited in us was full of empathy. The tears some of us shed came from knowing and understanding her. There is nothing quite like the impossibility and beauty of mixedness.

My tears from Saturday turned into words which turned into a poem on Sunday.

——————————————————————-

you can’t fathom

the

different

borders

boundaries

lines

divisions

compartments

departments

cultures

languages

phrases

teams

dreams

realities

victories

visions

feelings

perspectives

lessons

directives

dwellings

&

expectations

that I meet and master

simultaneously

built custom to the second

minute

hour

day

week

month

year

and decade when necessary.

I am practically a deity

with 50 arms

and endless fluency.

if I tried to explain it,

I woud fail

if I tried to show you,

I would collapse

and if you tried to be me,

you would fall fast, with bold blows to the

heart and head.

God must be MIXED

into me because I perform

miracles.

I do the impossible- braid together

souls that I was shown didn’t function in the same universe.

I surf prohibited oceans for fun

and flip the sky over just to see the other side.

I risk everything all the time

in name of my duty to myself.

I know no other way to spin the world

other than in between

planets causing chaos by meeting.

my name is hard to say

and it pains me to answer questions

but I am the only one I know who can

carry me.

Who can shape faces empathetically into family

when we are at war.

Who can take a house apart and reconstruct its

framework while sleeping.

Who can undo the haters

with the blink of the spirit.

Who can teach her parents.

I am skilled

highly qualified

and bursting with

sight.

If you tried to feel this

you might

cry for longing

your old home

with clear exit signs

and a fixed menu.

Change is the name of

my being

and adaptation

is clarity

in the form of

process.

Respect the dynamics

of a heritage of

shapeshifting.

Camila Lacques-Zapien is a multiethnic woman of color born and raised in Los Angeles committed to local community organizing, youth empowerment and arts education thanks to her passion for social justice and artistic expression. She is an avid poet, blogger, and world traveler. She studied both Chicana and Chicano Studies and International Development Studies at UCLA (’14) and co- founded the Mixed Student Union at UCLA in 2010. She currently works in education serving high school aged youth in Los Angeles and is preparing for her move to Italy for a Fulbright English Teaching Grant for the 2016-2017 cycle. You can follow her writing and reflections at: https://lacamilatlzblog.

Camila Lacques-Zapien is a multiethnic woman of color born and raised in Los Angeles committed to local community organizing, youth empowerment and arts education thanks to her passion for social justice and artistic expression. She is an avid poet, blogger, and world traveler. She studied both Chicana and Chicano Studies and International Development Studies at UCLA (’14) and co- founded the Mixed Student Union at UCLA in 2010. She currently works in education serving high school aged youth in Los Angeles and is preparing for her move to Italy for a Fulbright English Teaching Grant for the 2016-2017 cycle. You can follow her writing and reflections at: https://lacamilatlzblog.

Nicola Codner is 34 years old and currently training to be a person-centred counsellor in Leeds, UK. She is biracial and her heritage is White British and Black Caribbean. She has a strong interest in difference and diversity which led her into re-training as a counsellor. Prior to training as a counsellor she worked as a publisher in academic publishing. She’s keen to continue to develop my writing experience hence part of her interest in blogging. She has a degree in English Literature and Psychology.

Nicola Codner is 34 years old and currently training to be a person-centred counsellor in Leeds, UK. She is biracial and her heritage is White British and Black Caribbean. She has a strong interest in difference and diversity which led her into re-training as a counsellor. Prior to training as a counsellor she worked as a publisher in academic publishing. She’s keen to continue to develop my writing experience hence part of her interest in blogging. She has a degree in English Literature and Psychology.

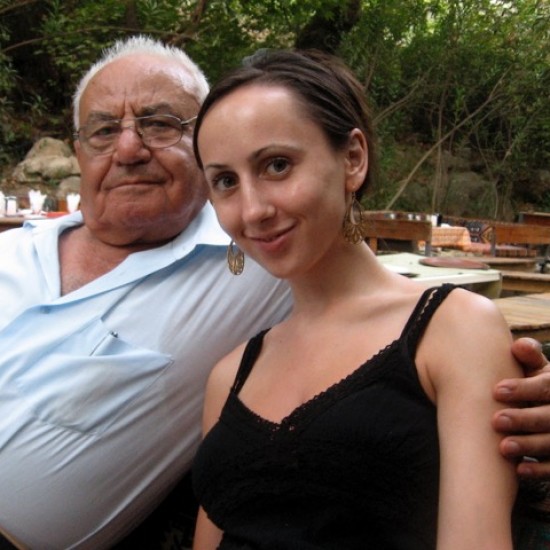

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.

Sarah Gladstone is a writer based out of Oakland, California. In addition to being a contributor for online sites such as Ravishly and The Huffington Post Blog, she also works on personal writing endeavors. WHITE DADS, a new zine anthology of stories, art, and experiences told by people of color fathered by white men, is her most current project. Most of her writing is creative nonfiction, poetry, and prose on topics relating to identity, race, and orientation. She appreciates all great forms of storytelling, magical realism, and the interconnectedness of art with social justice and humanity. When she’s not entangled with the written word, you can find Sarah debating the merits of pop culture, indulging in discount cinema, and generally trying to live a story worthy life.