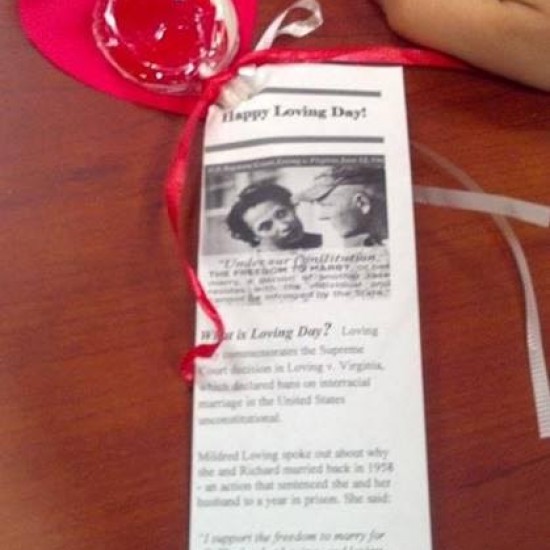

My mother was 20 when she gave birth to me. She was a single white woman holding her newborn brown baby at St. Mary’s Hospital, and I don’t really know what she was feeling at the time because I haven’t thought to ask her before now. I wonder, though, how her singleness, her age, and her race colored her experience of welcoming me into the world. Did my mother endure criticism because she was a young, unwed Catholic woman, just a couple of years past high school? Did she face a similar situation to the one Rebecca Walker describes in her memoir Black, White, Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self? Walker writes of reading the one-word question “Correct?” next to her parents’ races on her birth certificate, as if someone couldn’t fathom the possibility that a black and white union was not a mistake. I imagine—and like to think—my mother didn’t consider her status or age or race at all; instead I picture her overcome by sentiments new mothers typically feel—joy and relief and exhaustion, untainted by the world outside of the space between her eyes and mine.

I’ve also not thought to ask my mother how the social considerations of marital status, age, and race affected her as I grew older and as she mothered me in various contexts through the stages of my life. As a child, I thought nothing of the fact that my mother was unmarried, and I remember telling a playmate that I had no dad—really believing that I had no father, that my mother had sprouted me the way a plant shoots out a rhizome. I thought it was cool that my mother was so beautiful, strong, and younger than all the other mothers. And race? I didn’t know a thing about it for a long time. Not surprisingly, my first knowledge of it came through the issue of color. Still, my mother’s color in relation to mine never crossed my mind. My first awareness of color was of my color, perhaps because my mother’s was the same as the majority of people I knew, growing up in white communities as I did. So, in my childhood eyes, I was the different one. And for most of my childhood, I felt special in that difference rather than peculiar.

On a few occasions, though, people would ask me if I were adopted, and at those times I felt very peculiar—both unmoored and confused. Could they not see my mother in me? My upturned nose just like hers? The same crooked canine tooth? Our similar voices and mannerisms? And now I wonder, did my mother face similar questions? Did she encounter people who questioned her relationship to me, either benignly or aggressively? Were people ever hostile toward her when it became clear that she, a white woman, had paired with a black man? And what were the challenges she faced, both race-related and otherwise, as a young single parent?

These questions have only just begun to occur to me since I have become a mother. Unlike my own mother, I was married and in my 30s when I had my daughter. Also, my daughter and I share brown skin and therefore don’t face external questions about who belongs with whom. (In fact, at her school orientation, when I entered the room where my daughter was playing, another child turned to her and said, “Hey, brown girl, your mother is here.” Nope, no confusion there. Yes, I’m being both straightforward and ironic.) I am still challenged by motherhood and curious about my own mother’s experience and the way singleness, age, and race affected it. What I know is this: mothering is tough; single mothering tougher still. And here’s how I know:

It’s 5:00AM on a Tuesday morning, and my daughter calls to me from her bedroom. “Mom, I don’t feel well!” I leap out of bed, bang my foot on the nightstand, and limp across the house to her room. With one hand on her forehead, I know the deal: fever, sick day, no school for her…and no work for me. After the thermometer, the cool washcloth, the lullabies, she’s sleeping soundly again, but I know I won’t be able as the sun inches its way toward day. I sit before my computer and email all the necessary parties: her school, my students, the administrative assistant in the department where I teach. Then, I need to pore over my syllabi, making sure I can squeeze back in the work that will be missed today.

How much of this is familiar to you, women of the world? Whether you’re like me, a now-single mother, or whether you have a partner, most women with children are familiar with the scenario I describe. Historically, women have raised children. Women have been responsible for their feeding, for their entertainment, for their care when they’re sick. Across generations, across cultures, across races. Even when we work. We know this. And even the television commercials remind and train us in our role so that—often unthinkingly—we assume our place in the familial scheme.

I recall a particularly telling moment after my daughter’s father and I were separated but before we were divorced. Our child was visiting him for the night, and he called me (5:00AM again) to let me know that she was sick. “I’ll drop her off before I go to work,” he told me. What?! “Wait a minute,” I balked. “I teach today…”

But that wasn’t really an issue to him, and even I felt conflicted about my duties. I want to excel in my career and, in fact, I love my time in the classroom. I take my students and our plans seriously and don’t cancel classes lightly. At the same time, I strive to be an exceptional mother (don’t we all?), and I feel there’s no better place for my daughter to be than with me, especially when she’s sick.

“She’s sick. She needs to be with you,” he added, and this “compliment” was so well aligned with our cultural expectations, with my expectations of myself, that I quickly relented any opposition I might have entertained. Yes, I’m her mother; she’s my priority, I understood. “Bring her back,” I told him.

So today, when V. awoke feverish and needy, I knew I was expected to email her father and let him know her condition. I’m obliged to keep him apprised of her health when it’s abnormal, of unexpected visits to the doctor, of diagnoses that are made. Dashing off a business-like email to him, I felt highly conflicted about my position. Yes, I want to care for my daughter. No, it’s not right for me to hold the sole responsibility for her care, whether this responsibility has been imposed on me, assumed by me, or a little of both. I felt the itch of resentment, thought he should at least offer to take her to the doctor, if necessary, so that I could teach my classes today. Still, I didn’t really expect him to offer. I am her mother; she is in my care.

Now, I don’t want to be misunderstood here. I’m not suggesting, nor do I believe, that there aren’t plenty of balanced, mature, nurturing men in the world. Many of these are the hard working, committed partners of hard-working women; others are the often culturally forgotten single dads who work as hard as single mothers. I know many very committed and caring men who are admirable fathers and equitable partners.

Nevertheless, we can recognize that historically childrearing was women’s work, and in many cases it still is. And I’m not denigrating this task in the least. I know mothers do some of the hardest work that is ever done and surely the most primary, if not the most important (though I would throw my hat into that argument any day). And we know well the gains that the second wave of feminism offered in giving women choices regarding motherhood and career. Additionally, as third wave feminist Rebecca Walker has pointed out, while the second wave gave the following generation the choice, the third wave recognized that it was perfectly acceptable for a woman to choose motherhood over career if that was personally most fitting for her.

The third wave also allows us to recognize, though, that often the either/or choice is not the one that is made; many times, we women still want it all. I, for one, want to teach, research, publish AND I want to be the main caregiver of my daughter, have a from-scratch meal on the table for her every night, and keep the house pristine. Women like me are trying to embody what Michelle Wallace called in the 1970s the “myth of the superwoman,” and we’re suffering for it.

How? Well, I return to that internal struggle I feel about the care of my daughter when she’s sick. I sincerely want to be with her, and I recognize that I have a job to do. As the breadwinner, my job puts the food on the table; it is a fundamental resource in the very care I take of her. If I were to request that her father take her for the day while I work, I might suffer, however irrationally, a sense of inadequacy, as if I can’t do without him after all—and believe me, I’m not one to suggest that. Or as if I am somehow less of a mother if my care isn’t focused squarely on nurturing—on the cooking of chicken soup, tucking in of covers, and signing of songs.

Clearly, there are some problems with these nagging thoughts of mine, but am I alone in thinking them? I doubt it. Yet this self-awareness is useful. First of all, I’m coming to recognize the importance of support (Really? you ask me. You’re just now figuring this out, Superwoman?). Whether I want to accept her father’s support or not (and whether or not he would offer it), I am realizing that I do need others to have my back as I raise my daughter. That old cliché is true: it does take a village. I recall my own childhood again, and my maternal grandmother coming to live with my mother and me when I was six. She picked me up from school, cooked our meals, cleaned the house; in a way, my mother did have a parenting partner, and all three of us benefitted greatly. Considering this, I’m grateful for close friends in my life, for the welcoming school my daughter attends, for family a phone call away.

The second problem is a bit harder to rationalize my way out of, as motherhood has been so linked with nurturing. Whether my idealization of the mother care-taker is culturally conditioned or biologically inherent isn’t really the issue for me; rather, I recognize that, as her mother, I love to nurture my daughter, and I believe the sense of maternal security I provide can and hopefully will be an imprint that sustains her as she grows into a woman capable of mothering herself.

Speaking of mothering the self, I’m reminded of a scene in one of my favorite novels, Toni Morrison’s Jazz. After Violet’s husband has an affair, she and Alice converse about womanhood, life choices, and maturity.

Violet says, “We women, me and you. Tell me something real. Don’t just say I’m grown and ought to know. I don’t. I’m fifty and I don’t know nothing. What about it? Do I stay with him? I want to, I think. I want…well, I didn’t always…now I want. I want some fat in this life.”

Alice replies, “Wake up. Fat or lean, you got just one. This is it.”

“You don’t know either, do you?” Violet challenges her.

“I know enough to know how to behave.”

“Is that it? Is that all it is?” Violet is forced to ask.

“Is that all what is?”

And then Violet jumps in with my favorite line: “Oh shoot! Where the grown people? Is it us?”

“Oh, Mama.” Alice utters.

I love that exchange; it’s poignant and it’s real. How many of us, despite motherhood and seeming maturity, still don’t feel old enough or wise enough or capable enough to mother? We wonder if we’re mothering “right.” We wonder if we’re there for our children enough, if we’re teaching them well, if we’re guiding them wisely toward emotional intelligence and five fruits and veggies a day. Many of us look to our mothers, as I do, imagining they had all the answers by the ripe old age of 35. Like Violet and Alice, we look around and wonder where the real grown ups are and then sit back, stunned, calling for Mama when we realize we’re the grown people, even when we feel like imposters.

Perhaps we should take some comfort in that fact, in the realization that all of us—and our mothers, too—feel like imposters from time to time, but that’s only because we haven’t been down before whatever road it is we’re traveling. We haven’t yet encountered whatever challenges—in relationship, in age, in cultural codes, in you-name-it—that are still coming down the pike. That’s the point, though, right? We keep the growing edge of ourselves alive; we keep living and learning, trying and failing or succeeding, always facing the new questions that arise. As Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “There are years that ask questions and years that give answers.” So even when we have to live the questions for longer than we’d like, perhaps we can comfort ourselves with the fact that, eventually, we will live ourselves right into the answers.

It seems to me my mother did. And I’ll be sure to ask her.

By: Tru Leverette, PhD.

[rescue_column size=”one-fourth” position=”first”] [/rescue_column] Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.

[/rescue_column] Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.

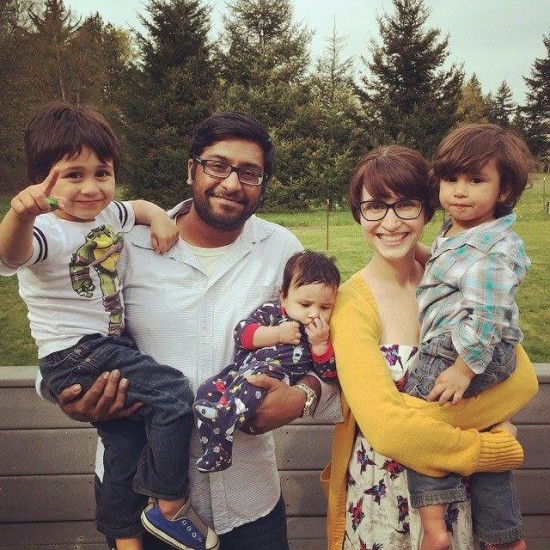

Brittany Muddamalle is the mother of three boys under four years old. She has been in an intercultural marriage for six years. Her and her husband are currently raising their children in American and East Indian culture. She is also the writer of The Almost Indian Wife blog. Her hope is to make a change by sharing her experiences with her own intercultural marriage and raising biracial children.

Brittany Muddamalle is the mother of three boys under four years old. She has been in an intercultural marriage for six years. Her and her husband are currently raising their children in American and East Indian culture. She is also the writer of The Almost Indian Wife blog. Her hope is to make a change by sharing her experiences with her own intercultural marriage and raising biracial children.

[/rescue_column] Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.

[/rescue_column] Tru Leverette works as an Associate Professor of English at the University of North Florida where she teaches African-American literature and serves as director of African-American/African Diaspora Studies. Her research interests broadly include race and gender in literature and culture, and she focuses specifically on critical mixed race studies. Her most recent work has been published in Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora and the edited collections Other Tongues: Mixed Race Women Speaking Out and The Search for Wholeness and Diaspora Literacy in Contemporary African-American Literature. She served as a Fulbright Scholar at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, during the Winter 2013 term.