I’m mixed – African American and Irish. My mother is Black – I was raised solidly within the African American culture alongside a firm understanding and embracement of my Irish roots. Both sides of my heritage are steeped in oppression and slavery – histories that people want to forget and ignore. I have been told by my Black friends I have “that good mixed hair,” “that good light skin,” and “dem good pretty eyes.” I know I’m different – I’ve been told that my entire life from family, friends, and teachers – sometimes even strangers when they do the inevitable “guess Deanna’s race game” without my permission. People pass by me on the street or in the mall and they see one of two things: I’m Black with something or I’m Dominican with something; it’s never that I’m White and something.

With the entire world knocking at my door with my “otherness,” feeling the necessity to exclaim that I am not White alone, why do I feel unwelcomed in the conversation surrounding #BlackLivesMatter? Why have I gotten into multiple arguments with – mostly – Black women on Facebook telling me I’m not allowed to be a part of the movement because of my light skin and nice hair? Because of an assumed privilege both of those phenotypic qualities, among others, may or may not have given me in life? Because they assume my mother is White and did not raise me within the lens of a Black person in the United States (not that I’m saying whatsoever that mixed race peoples with White mothers deserve less access to this movement – this is just an argument I’ve gotten into with another Black woman)? Why am I devalued in the eyes of African Americans (most of whom, sorry to say, have White in them thanks to the prevalence of rape during slavery) when I have just as much soul, anger, and desire for equality as they do?

An article written by Shannon Luder-Manuel, a mixed race writer in Los Angeles, really hit me hard with her opening line: “When I talk about my family culture, I’m mixed. When I talk about racism, I’m black”.[1] Praise God, Hallelujah, Shannon you just said what we’re all thinking – we as mixed raced individuals live on this tight rope where if we lean to one side we identify ourselves mixed and embrace both sides of our heritage, but on the other side we have the option to choose which portion of our heritage we want to fall upon. When Trayvon Martin was murdered back in 2012, I was in my first year of undergrad. I cried for days. I saw in him my cousins – Black men I had been raised with and loved by and guided by my entire life. I saw in him my future children – kids who, regardless of the race I marry, will be “others” just like me, just like Trayvon. When Sandra Bland was murdered for a failure to signal, I saw myself – a woman of color who forgets to do the boring tasks while driving. I have never been pulled over (knock on wood) but I have never been as terrified or aware as I am today.

I’m not trying to say that my ambiguous looks do not give me some headway in regards to potentially being harmed by police brutality – I know I confuse people and that’s in my best interests. I know that because White people can’t pinpoint my exact ancestral heritage (I’ve gotten as far out as Indian mixed with Dominican), I have a better chance at not being targeted for the historical no-nos for Blacks, such as DWB (Driving While Black). I know my designer clothes (because my mother buys them for me, I’m poor guys) and my fancy car aid in my assimilation into the “White” culture. I know that the preference for my lighter skin and fluffy curls, both within and without the Black community, puts me at the head of most ethnic status quos. However, even with these “privileges” (I don’t necessarily see them as such because the fou

ndation for my body is still “other” and I will never, ever be able to fully be accepted by the White community) I am still at risk, my family is still at risk, my future family will still be at risk – as long as my body and the bodies directly connected to me, now and in the future, are deemed as “not White,” I will forever fight for the Black Lives Matter Movement.

When the whole of the Black community accepts me – and others with the same intentions and racial ambiguity as myself – the Black Lives Matter Movement will only grow stronger – it will prove to White people that nothing, not even the fact that someone has White directly in their ancestry, will break us. We will always stand together and we will fight until our bodies and the bodies of our loved ones are protected against outside harms. Are we Black enough ye

[1] See: Luders-Manuel, Shannon. (2015). “What it Means to be Mixed Race during the Fight for Black Lives.” For Harriet. Accessed August 9, 2016: http://www.forharriet.com/2015/08/what-it-means-to-be-mixed-race-during.html#axzz4Gt2dOOi3.

Deann a Keenan lives in Upstate New York and recently graduated from Binghamton University with B.A.s in Psychology and Africana Studies, with honor’s in Africana Studies. She is currently a Copy Editor for Africa Knowledge Project – a publishing house that has a wide range of journals that discuss various aspects of the African Diaspora. She is also currently the Guest Blog Coordinator for Mixed Roots Stories. She also holds a position as an Adjunct Lecturer at Binghamton University for the 2016-2017 school year, teaching Africana Studies 101. She has been published in the journal ProudFlesh twice, with two pieces in production, and has presented at the American Public Health Association (November 2015). She hopes to continue her education in Developmental Psychology, researching Mixed Race identity formation, among other topics regarding the population.

a Keenan lives in Upstate New York and recently graduated from Binghamton University with B.A.s in Psychology and Africana Studies, with honor’s in Africana Studies. She is currently a Copy Editor for Africa Knowledge Project – a publishing house that has a wide range of journals that discuss various aspects of the African Diaspora. She is also currently the Guest Blog Coordinator for Mixed Roots Stories. She also holds a position as an Adjunct Lecturer at Binghamton University for the 2016-2017 school year, teaching Africana Studies 101. She has been published in the journal ProudFlesh twice, with two pieces in production, and has presented at the American Public Health Association (November 2015). She hopes to continue her education in Developmental Psychology, researching Mixed Race identity formation, among other topics regarding the population.

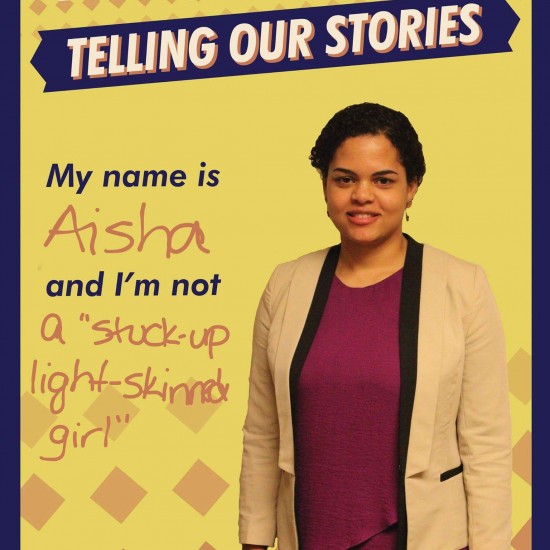

Aisha Springer is based in Baltimore. Her writing primarily focuses on issues of race, feminism, and personal essay. She is a Contributing Writer for Hashtag Feminism, a blog examining feminist topics through a media lens, has written book reviews for STAND, the ACLU magazine, and was a 2015 Social Good Summit Blogger Fellow for the United Nations Association (UNA-USA). During the day, she works full-time at a civil rights nonprofit.

Aisha Springer is based in Baltimore. Her writing primarily focuses on issues of race, feminism, and personal essay. She is a Contributing Writer for Hashtag Feminism, a blog examining feminist topics through a media lens, has written book reviews for STAND, the ACLU magazine, and was a 2015 Social Good Summit Blogger Fellow for the United Nations Association (UNA-USA). During the day, she works full-time at a civil rights nonprofit.